The Black History of Prairies, Post by Ivy Clark, photos as attributed.

Lauren ‘Ivy’ Clark studied the hybridization of Castilleja levisecta and C. hispida in restoration sites for their Masters thesis at the University of Washington before becoming a restoration technician for the Center for Natural Lands Management.

The Black History of Prairies

Caveat: I want to first address an elephant-sized grain of salt to take while reading this. I, Lauren “Ivy” Clark, author of this post, am not Black. My skin is White to the degree that parts never seeing the sun are more like translucent. I need plenty of sunscreen on the prairies, yes. I will try to resist any urge to get on a soap box here or attempt to lecture and certainly cannot speak from experience regarding feeling the historical wound of racial discrimination. I think this information on the Black/African-American history of the prairie ecosystem is interesting and pertinent and should be shared. I am always in favor of sharing factual information because, as you may have guessed, I am a nerd.

On a whim, I decided to look into any history I could find (easily) about a connection between prairies and Black history, since February is Black History Month, and the past year has seen so much racially related news. It seemed like a good time to learn something new in that topic. I did not already know of any link between the two but it was worth a look. Now, my first search yielded information on cute critters like the black-tailed prairie dog, and black-footed ferrets. See pictures below (from Wikipedia).

Blackfooted Ferret and Black-tailed Prairie Dog, photos from Wikipedia

Adorable yes; not what I was going for. I searched for any publicized Black researchers working on prairies which only led me to many graduates of a “Prairie View A&M University” which I had not heard of before but I like the name. Then I found a book titled “Black Prairie Archives: An Anthology” by Karina Vernon of the University of Scarborough as a culmination of a PhD thesis and subsequent research. That lead me to a documentary called “We Are the Roots: Black Settlers and Their Experiences of Discrimination on the Canadian Prairies”. Bingo! It opens with this quote: “In 2017, 19 descendants of the Black settlers from Alberta and Saskatchewan were asked to discuss their experiences of discrimination.” The story is one of creating rural farming communities cut straight from the tall grass Canadian prairies. And it goes a little something like this:

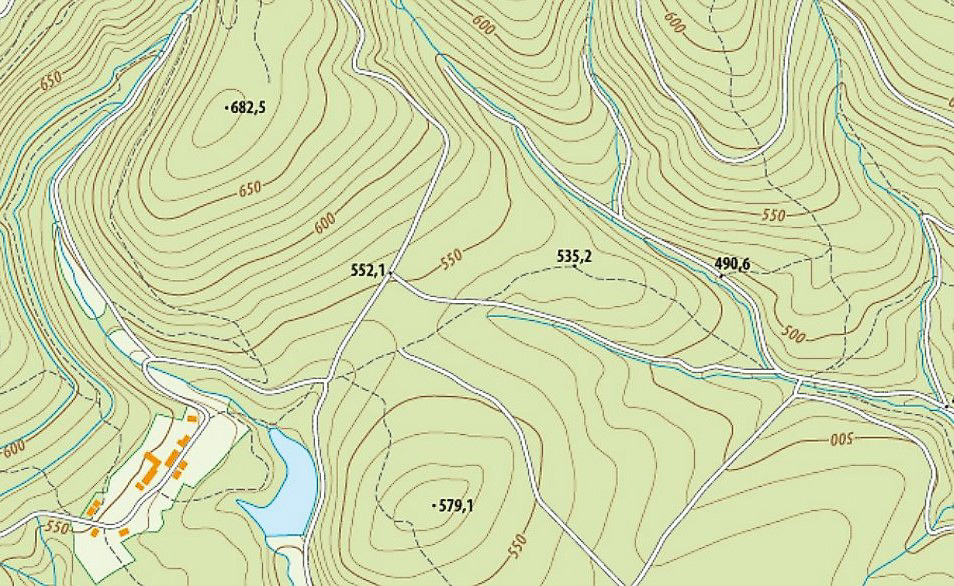

Not a photo of an Alberta prairie, but it is a northern site with prairie species, Dan Kelly Ridge near Port Angeles. Photo taken by Ivy Clark.

In Alberta in the early 1900s there was a call for people to come homestead the wild region, and over a thousand African Americans left Theodore Roosevelt’s America to immigrate to western Canada. Thousands of advertisements were sent to America from the Canadian government beckoning people to move to the “Last Best West” to purchase 160 acres of land for a fee of $10. Wow, don’t you wish that were still available, even after inflation? From a distance, it seems like a great time in the US though, with the Ford Model T hitting the market and Albert Einstein publishing his “Theory of Relativity”, and the Wright boys building the first powered flying contraption. Then again there was the whole Titanic tragedy and the largest industrial accident of US history killing 361 coal miners in West Virginia, then the infamous Shirtwaist Factory fire (another of the largest industrial accidents in our history, leading to changes in safety for workers). So there were ups, and there also were downs, perhaps those naturally following ‘going up’ too fast with too many unknown factors.

Flier examples of the call for Canadian settlement. From We Are the Roots.

But that zoomed-out history does not reflect the experiences of African Americans, not long emancipated after the Civil War. The societal push back against that, more so in the southern US, was harsh and accelerating; cue the Jim Crow laws. President Abraham Lincoln declared African Americans free from slavery but it wasn’t like they instantly got all the same rights as every White American. Culture and laws are not like a video game with an ‘undo’ button that changes everything. At the time, only about 20% of African Americans owned their homes compared to the roughly 50% of White Americans. During the Civil War it was North vs South with the North being in favor of African American freedom, so one could presume a general favorable view of anything “northern” for Black people. And living in the south was growing not just difficult but rapidly more dangerous, with violence and lynching on the rise. So when Canada said, [insert friendly Canadian accent] “Hey there, wanna come up here and have a home and land to expand our country, eh?”, it’s understandable a large group of African Americans packed up and moved over the northern border, leaving predominantly from many southern states.

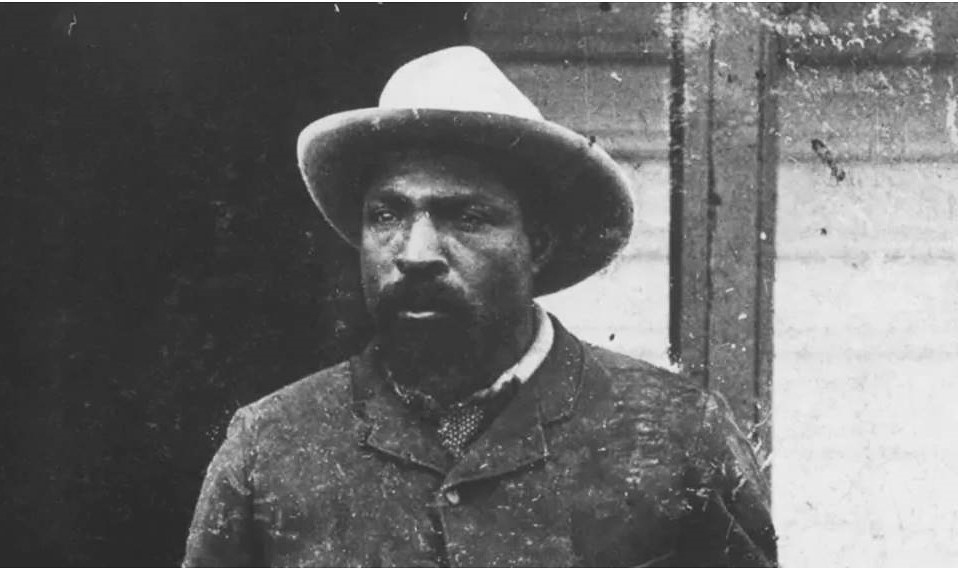

Snapshot from documentary with actor depicting John Ware, late 19th century immigrant and rancher. From John Ware: Reclaimed.

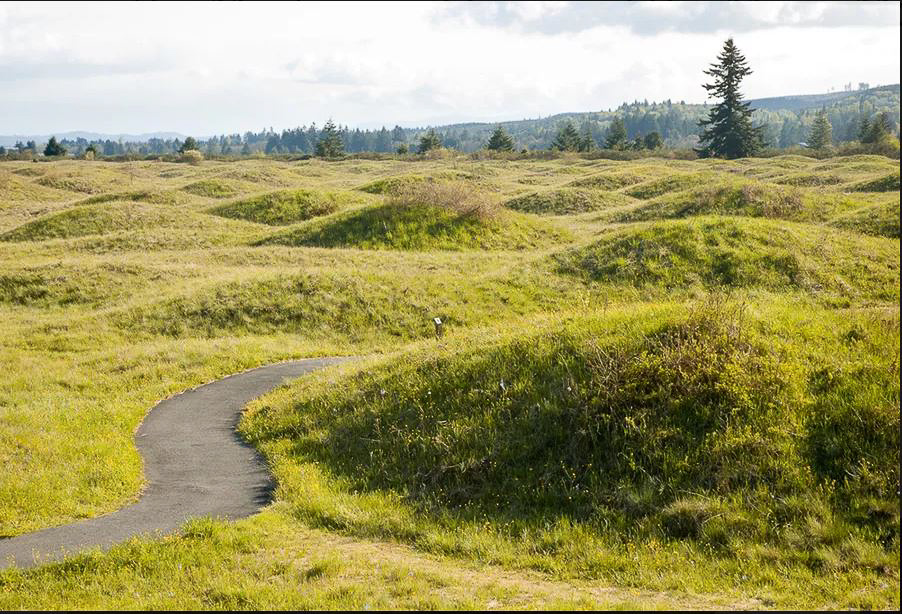

Not that Canada was an all-welcoming nation with nothing but big bear-hugs for all. The advertisements were not specifically targeted to African Americans, so crossing the border wasn’t always smooth; petitions against this immigration were sent around, and in 1911 the Boards of Trade convinced the Prime Minister to prohibit any further migration of such folks. That legislation didn’t last long and already a large number made it through. They were again segregated from White people, like the Jim Crow US south. This initial separation created communities of mostly Black people in western Alberta and Saskatchewan, the largest being Amber Valley with 300 Black settlers and three White immigrant families, living together without conflict. Life was rough, clearing farming land, building homes and schools with cut timber. But there were also dances and huge summer cook-outs that drew people from many miles away. Children played in the adjacent untouched native prairies with the tall waving grasses reaching above their heads. They played with rainbow-colored foxtails and walked along the railroad tracks until the heat & smell of metal was too strong in the sun, opting then to amble slower through the sweet flowers of the open prairie. Interviewees, those children grown now into elders, talked a lot of integrated communities and help from neighbors, including the White ones, and of integrating immigrants from distant nations as well. Everyone generally just wanted to get along and get by because they were all equally new in this wild and beautiful rural area.

Homestead in western Canada prairie with recently cleared farmland near a tree lined river. From We Are the Roots.

Life on a Canadian prairie would see more extremes than our milder Washington prairies. The southern pioneers had to adjust to new farming patterns due to the more severe Canadian winters, but still they thrived. Plentiful wild game in the area made up for lower farm yields. Created on very isolated lands, these communities were hewn straight from the local timber with tree branches for school bench legs. They helped build these western Canadian provinces into what they are today. Yet over time, especially during the Great Depression, the community populations declined as families moved to neighboring cities for work. But the prairies were the safe harbor against discrimination and violence.

Alberta’s rural areas left behind. Photo from Flicker open source.

The early 20th century migration was not the beginning of Black people in Canadian prairies. There is documentation of Black fur traders and voyageurs since the 18th century. And today prairies have the fastest growing population of Black people in Canada.

For the classic western fans, you may be interested in a recent documentary about essentially a Black John Wayne- the famous John Ware. John Ware: Reclaimed documents a Canadian prairie icon, a Black cowboy known even among the local indigenous tribes for his horsemanship skills. He arrived in Alberta in 1882 with the first cattle drive there. Ware was a charismatic skilled rancher owning a thousand head of cattle. Even John’s wife Mildred was iconic, being the first Black woman writer on the prairies.

Photo of cowboy John Ware. From John Ware: Reclaimed.

Today there of course is still racism in these regions of Canada. It’s more subtle than in the US, but the journey to equality continues much like everywhere else. The Canadian Black settlers are larger scale story of community and prairie homesteading, similar to our very local Black figure- George Bush (whose middle name was once thought to be “Washington” but found incorrect, perhaps a homage to his part in settling the state or for the president in office at the time of his birth). George and Isabella Bush arrived in the Washington Puget Sound region in 1844 with their four sons in tow and two more born after. George Bush (no relation to the president I assume) brought his and four closely connected families along the Oregon Trail in a wagon train from Missouri. George had already done fur trapping in the western regions and figured the west would be a good escape from southeastern discrimination. He thus was a very useful leader for this first non-indigenous group to settle north of the Columbia River. Originally intent on the Oregon Territory, but with discriminatory legislation having arrived first, the group turned their wagons north to what was then a territory of both the US and Great Britain. The group established Bush Prairie community, farming near present-day Tumwater, WA and building the region’s first sawmill and first gristmill. After Washington became an official US territory in 1852 and the adjoining discriminatory US laws took hold, the Bush’s weren’t legally permitted to own the land they settled. Thanks to the Bush’s friendship with the new Washington Territory Legislators, there was a unanimous vote in 1855 to allow this Black family to have official ownership of their farm of 640 or more acres. This made George the first African-American landowner of Washington State. Part of their homestead is now the Olympia Airport in Tumwater. Keep an eye out for their namesake and history and take a look at the last five acres of historic Bush Prairie Farm, protected as of 2017 by the Capitol Land Trust. The farming skills of the Bush family still show in a grand butternut tree they brought west from his farm in Missouri which is now 174 years old and probably the oldest living butternut tree in the world. It even has a good size offspring now planted at the Capitol grounds (check out this link for fun details). The Bush family was well known for their generosity, giving away some of their own food stores to new settlers, further helping build a successful community and friendship around them. Let us try to remember this founding principle as our now much larger south Puget Sound prairie community grows and overcomes new challenges, while still holding on to as much native prairie as we can.

Photo of three generations of Bush family on their Bush Prairie Farm, date unknown. From Historylink.org.

The prairie landscape doesn’t care what color you are. It is a place of huge natural biodiversity with complex interactions of many species. Every landscape and community benefits from diversity of all kinds. Take a tip from ecologists who know that is great for building a more robust resilient system. If our South Sound Prairies were ONLY camas, as lovely as those are, it would be vastly less beautiful without the yellow spring golds and buttercups, white field chickweed, pink seablushes, golden fescue inflorescence or occasional evergreen kinnikinnick patches.

Diverse beauty of prairie flowers and golden paintbrush plundered by a bumblebee. Photo taken by Ivy Clark.

If you would like to watch the moving documentary of Canadian Black immigration for yourself, the link that follows will take you there. https://vimeo.com/257364347

Photos sourced from author, cited materials, or Flicker open source.

Sources Used:

https://eh.net/encyclopedia/african-americans-in-the-twentieth-century/

https://sos.oregon.gov/archives/exhibits/black-history/Pages/families/bush.aspx

http://www.bushprairiefarm.com/bush-farm-history.html

https://capitollandtrust.org/bush-prairie-farm-now-protected-forever/