Editor’s Note: I was supposed to get this posted yesterday. Now you’ll have to wait for the snow to go away or do some digging. At least the snow will protect the young seedlings from the very cold nights predicted the next few days.

Seedlings to See Now, Post and Photos by Ivy Clark

Lauren ‘Ivy’ Clark studied the hybridization of Castilleja levisecta and C. hispida in restoration sites for their Masters thesis at the University of Washington before becoming a restoration technician for the Center for Natural Lands Management.

Seedlings to See Now

Doesn’t it feel like lately every spring starts trickling in too early, with plants peeking up through the soil well before you think they should? We have had a warmer January than usual this year. I am already seeing a lot of spring early-blooming species growing vigorously and we are not in spring yet.

So now that we are starting to stare at the ground, and feeling a bit obsessive about it (if you’re like me), first- stretch your neck & check out the clouds for a minute. Second- let’s refresh on a little plant anatomy so we can identify what seedlings and other young sprouts are emerging right now. That way, you can tell which plants are ‘friends’ and which are ‘foes’ while it is easy to clear away some foes to give extra room to the friends. Give the enemy no quarter. We’re going to focus on dicotyledonous plants (those with two “seed leaves”) aka- broad leaf plants as opposed to monocots (grasses, sedges, lilies, etc). It’s only because monocot seedlings are hard to ID with the naked eye.

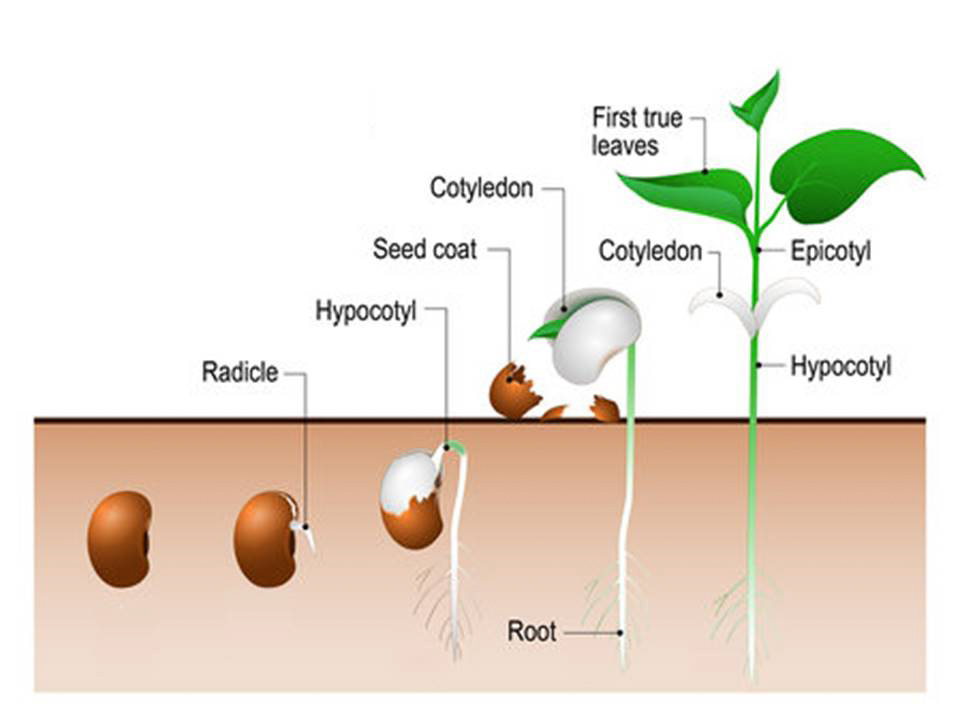

To know what seedlings we see pushing up through the soil we may need to refresh ourselves on seedling anatomy. Step 1 in germination is for the seed to absorb water so the embryo inside can start growing. That’s the wee little tiny baby plant that was dormant and waiting for a cue to awaken. That cue can be temperature change or just getting enough water to cross the seed coat to rehydrate the embryo tissues. Smaller seeds generally also need light to germinate because their smaller embryos won’t make it through a significant (dark) depth of soil before they run out of stored energy. A big seed like an avocado pit can grow 1-2 feet long before needing light for photosynthesis.

As the seed germinates, aka- makes a seedling, you will likely see two prominent parts- first the cotyledons and later some small true leaves, both on the young stem called first a hypocotyl (supporting the cotyledons) and then the epicotyl above the cotyledons that supports the true leaves. Cotyledons are very simple-structured “seed leaves”, having made up the major part of the seed. They are food storage for a tiny new shoot tip and the first root of the plant (the radicle) which are tucked between the cotyledons before germination. I think of cotyledons as the packed lunch provided by the momma-plant for its baby, and the bigger the lunch the bigger the seed thus the further it can grow before needing to make its own food via photosynthesis. Though cotyledons don’t give many clues to the identity of the plant, they do narrow it down a bit. It’s like seeing only a person’s feet and legs. Flowers are the face; the most useful in identifying a plant just like with people. But you can still get info from someone’s legs. Some are more athletic, longer or shorter, tanned or very pale. A professional hockey player will have different legs from a bikini model. Big thick cotyledons won’t be on an annual plant that makes many small seeds like a Collinsia but they would be present on a big perennial lupine.

The large fleshy simple cotyledons of a lupine seedling distinct among lush moss. Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.

Then of course the small true leaves will give us even more information about what species or at least genus the plant is because they will be the shape of the regular lower leaves you will see on that plant. Knowing all these clues, now we can start identifying some seedlings on the prairie. Location is of course the final clue since you probably won’t find non-invasive horticulture plants on a natural prairie. So a “wild lupine” (L. perennis) will probably not have jumped from the east coast to our western prairies, leaving one likely candidate for a big lupine-looking seedling we see there.

Speaking of lupines, Lupinus albicaulis is already popping up around their big remnant momma plants. They are probably our biggest seeds of the Washington prairie plants, looking like pea-sized pebbles. Below are two at progressively advanced growth showing the palmately divided leaf as it gets bigger.

Big young seedlings of sickle-keeled lupine (Lupinus albicaulis), with hairy cat ears around them. Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.

Other native seedlings popping up right now, and quite early we may add, include biscuitroot, buttercups, larkspur, pink seablush, bluebell, blue-eyed Marys, and (drumroll please!……) lady tresses! I only spotted the lady tresses seedling while looking closely at another species because it was so very small and looked at first like a less interesting non-native plantain. I was definitely talking excitedly to myself and our cutesy prairie orchid baby for several minutes. You know…like we crazy botanists do.

Western buttercup seedling (Ranunculus occidentalis) Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.

Weed vs wildflower, can you spot the difference? Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.

The spikey trichomes (hairs) of the leaves on the top seedling give it away as the invasive hairy and very prevalent false dandelion/hairy cat’s ear (Hypochaeris radicata), which I feel is misnamed because it looks more like a cat’s tongue. Don’t you think? Below to the right is what appears to be a native blue-eyed Mary (Collinsia spp.), an annual that is indicative of a prairie with enough disturbance like low-intensity fires to keep open ground for them to germinate and reseed. They have very round cotyledons with more elliptical first leaves which are similar to a young Hypochaeris but so very much less hairy and have more of a tapered tip from a fat middle of the leaf and a distinct short middle vein indentation. You can’t tell the difference yet between the species of Collinsia, grandiflora versus parviflora.

Another mix of native blue-eyed Marys (middle and lower right, I think) and an invasive ox-eyed daisy to far left and hairy cat’s ear to upper right. Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.

Perfect example of how much blue-eyed Mary associates with open ground, as a bunch of seedlings coming up at the cleared entrance of a small animal den. Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.

Not really a seedling any more, but a young Oregon sunshine (Eriophyllum lanatum). Note the narrowly elliptic leaves with velvety white hairs, no cotyledons anymore. Don’t be fooled by small plants in clumps as these are older growing up from rhizomes. Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.

Pink seablush (Plectritus congesta), not pink but a bright green on delicate thin boxy-round leaves with clear web veination, clearly smaller than the moss’s long sporophyte (the diploid stage of those plants). Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.

The biscuitroots were the first new growth I noticed this year, being so feathery and bright. They are typically one of the first plants to grow and bloom but this year is a bit accelerated. They were popping up in the middle of January. JANUARY! Kids these days…. Slow down.

Four seedlings of biscuitroot/spring gold (Lomatium utriculatum). See the non-lobed cotyledons? Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.

Larger seedling without cotyledons or possibly regrowth on a young rhizome. Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.

Distinct fluffy tufts of regrowing biscuitroot seen all over right now. Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.

Super early blooming biscuitroot. Spring gold? More like “late winter gold”. Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.

Upland larkspur (Delphinium nuttallii) seedling or young adult. Cotyledons are generally linear & simple. Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.

Another more red-edged larkspur with hairs visible along edges as well. Young Luzula comosa to the right as well, like a long-haired grass but more closely related to sedges. Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.

Young, possible seedling, of a bluebell/harebell (Campanula rotundifolia). Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.

Some older bluebells flanking a young seedling of hooded lady’s tresses (Sprinanthes romanzoffiana)*. Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.

This is likely an adult regrowing from its stubby finger-like bulb, but is still a lovely young hooded lady’s tresses. Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.

*I’m pretty sure that is what these plants are, but it is very hard to find any photos of the young leaves. It’s a bit shallow of plant photographers to only snap the sexy flower photos, if you ask me. So if anyone knows better, let me know. But from my long digging this is our local orchid Spiranthes. Notably they look most like the classic nursery orchids before the inflorescence stalk develops, then the leaves look more grass-like, which is what you see in all the photos available online. Changing that! These are the only monocots on the prairie with fat leaves ending in very bluntly rounded tips and with perfectly parallel linear veins along with what I think of as an alligator color pattern. They are very different from chocolate lilies or shooting stars or the more riparian fawn lilies.

The densely shiny hairy regrowth of a paintbrush (Castilleja spp.). Until they start blooming, you can’t tell which species (C. hispida or C. levisecta). Note the small bluebell and larkspur at bottom. Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.

Plenty of other plants are regrowing for spring now, like violets, yarrow, strawberries, saxifrage, and self-heal, plus vetches, ox-eye daisy and the various clovers not native to the prairie. But we’re focusing on the baby seedlings and I haven’t seen any of those natives as new germinants. Plenty of species germinate in fall as well, which is a common drought adaptation of going dormant in dry summer months then germinating and developing a good root system in fall and mild winter months to get a jump on spring growth later.

Strawberry’s common alternate form of reproduction which can create large patches of clones- stolon growth, shown as the long thin differently adapted stem connecting the top and bottom strawberry plants. Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.

Now that you know what natives to look for in the next few weeks, keep an eye out for these non-native seedlings as well. The sooner you can pluck the interlopers from where you don’t want them, the easier it is to make sure they won’t regrow. Invasive seedlings will also likely be at a more advanced growth stage, with plenty adults of perennials having not really gone dormant during our mild winter which we are technically still in. Can someone tell these seedlings that? They think it is April.

Sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella) with very identifiable leaf shape. Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.

Sheep sorrel has probably the most easily distinguishable leaves on our prairie, looking like a fancy spear head though the cotyledons lack the basal lobes, so these may be from older roots instead of seedlings.

Scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius). Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.

Long young Scotchbroom, probably germinated in the fall and is making a run for bloom-status through our mild winter. Photo by ‘Ivy’ Clark.