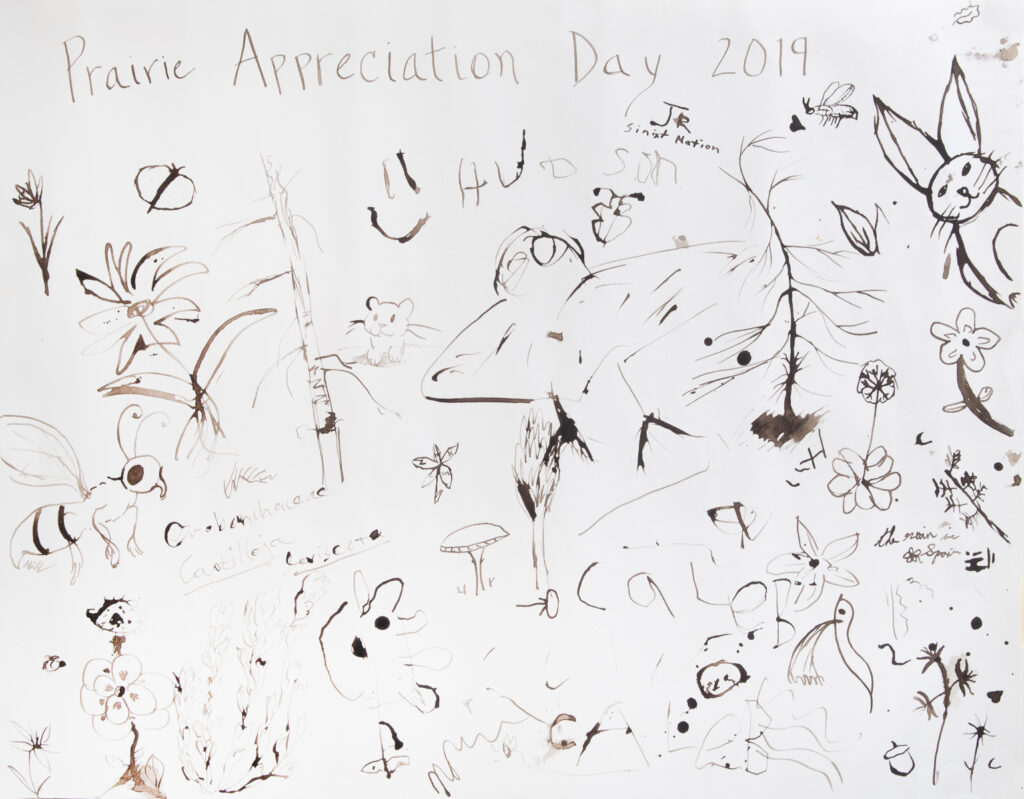

Special Note: Check out the home page for our plans for Prairie Appreciation Month: April 15th-May 15th.

Scot’s Broom Legacy Prairies, Post by Adam Martin, images as attributed.

Adam was part of the transition team that joined Ecostudies in 2020 after working on the South Sound Prairies since 2011. His work involves collaborative planning and implementation of restoration activities and developing research and monitoring projects to support the restoration and conservation of rare and federally-listed species in prairie and oak habitats in both South and North Puget Sound. He is currently in his candidacy in the Master of Environmental Studies program at The Evergreen State College. He is focusing on topics in conservation biogeography. His thesis work involves assessing the risks to native plant communities on small islands in the San Juan Islands.

Scot’s Broom Legacy Prairies

Illustration of Scot’s broom (Cytisus scoparius) from Köhler’s Medicinal Plants (1887)

Genesta [Scot’s broom] hath that name of bytterness for it is full of bytter to mannes taste. And is a shrub that growyth in a place that is forsaken, stony and untylthed. Presence thereof is witnesse that the ground is bareyne and drye that it groweth in. And hath many braunches knotty and hard. Grene in winter and yelowe floures in somer thyche (the which) wrapped with hevy (heavy) smell and bitter sauer (savour). And ben, netheles, moost of vertue.’ – A description of Scot’s broom (Cytisis scoparius) in the 1618 London Pharmacopoeia, quoted in A Modern Herbal by Margaret Grieve

Like the remaining meadow habitats in the British isles and Ireland, the first European settlers to the South Sound region likely considered the remaining upland prairie habitats we have today, at places like West Rocky, Mima Mounds, and Glacial Heritage as forsaken, stony and barren ground not fit for tilling. While such a dismal designation ended up being a blessing in disguise for the myriad of prairie species that remain, prairie species continue to be at risk from invasive and non-native species that are also well adapted to the same ‘ bareyne and drye’ habitats.

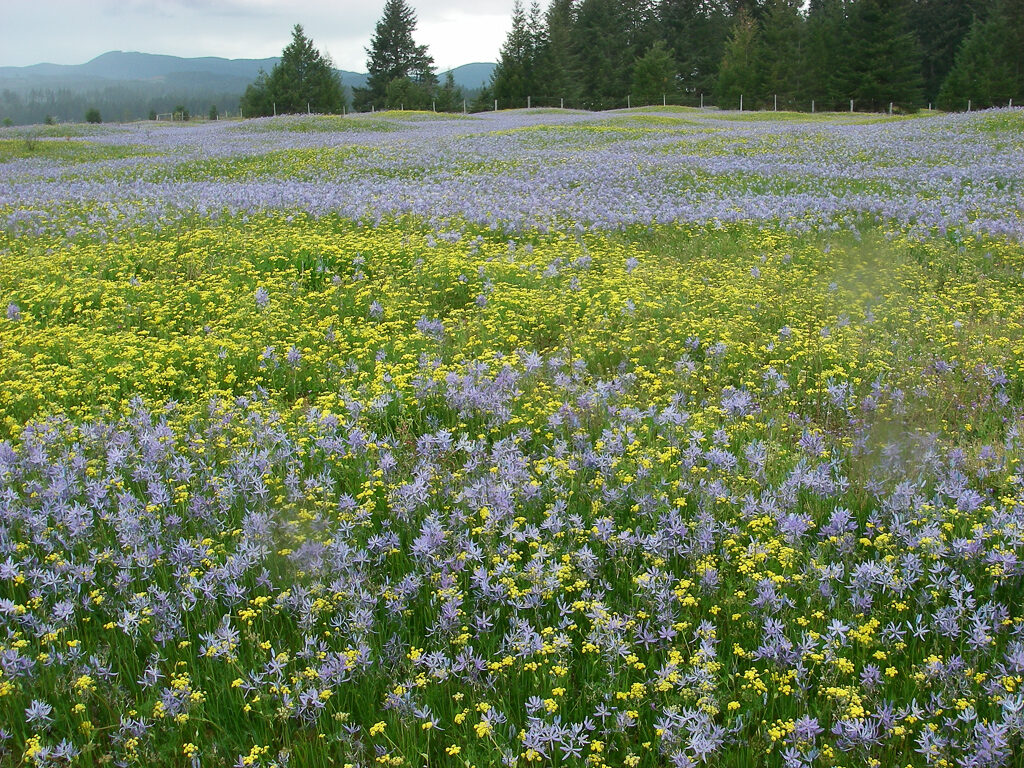

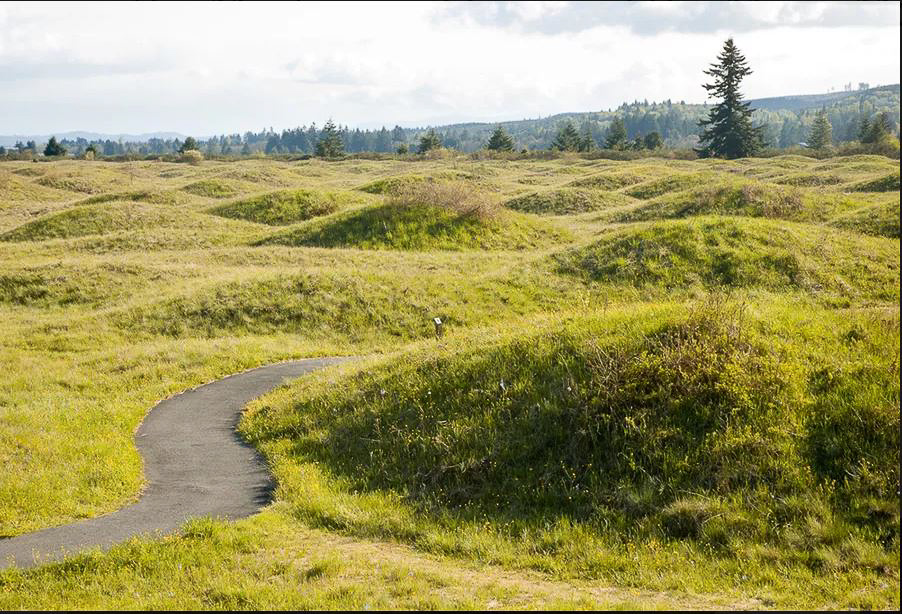

Remnant native prairie at Glacial Heritage that escaped invasion from Scot’s broom.

Most of our common prairie weeds, such as Scot’s broom (Cytisus scoparius), sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella), ox-eye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare), Colonial bent-grass (Agrostis capillaris) Yorkshire fog (Holcus lanatus), sweet vernal grass (Anthoxanthum odoratum), early hair-grass (Aira praecox) and shepard’s cress (Teesdalia nudicaulis) are native to the endangered grassland and meadow habitats of Britian and Ireland. Since our prairies and climate are so like the meadow habitats in the British Isles and Ireland, these weed species had a readily suitable environment to establish in. For example, shepard’s cress is considered Near Threatened in England where it grows in dry grasslands dominated by sheep’s fescue (Festuca ovina), a bunchgrass very similar in form and life history to our Roemer’s fescue (Festuca roemeri).

A degraded South Sound prairie or an intact English meadow? In the UK and Ireland, the suite of our South Sound Prairie weeds comprise a community of threatened meadow species. See more at widlifetrusts.org. Image source wildlifetrust.org.

The re-creation of European meadow ecosystems in a different part of the globe represents a very fascinating biogeographic story, and presents us with interesting conundrums like what to do when ‘our’ weeds are another’s rare ecosystem (a fact not lost on the late Arthur Kruckeberg). But, more importantly, the addition of so many European meadow species has caused the loss of much our own unique biodiversity, and re-establishing native prairie is the cornerstone of so much of the work we do on the prairies.

If there is one prairie weed species to rule them all, it would be Scot’s broom, which for decades spread across the South Sound prairies, changing our open grasslands to a thick shrubland.

Me standing in a dense thicket of Scot’s broom at Mazama Meadows while doing one of the first botanical surveys of the site.

Since the 1990’s, many of us have spent many days of sweat and tears cutting, spraying, mowing, pulling, and burning Scot’s broom. There is no greater testament to the tenacity of dedicated restoration than at Glacial Heritage Preserve. At Glacial Heritage folks have spent years of effort to liberate much of the prairie from the thumb of Scot’s broom’s shadow.

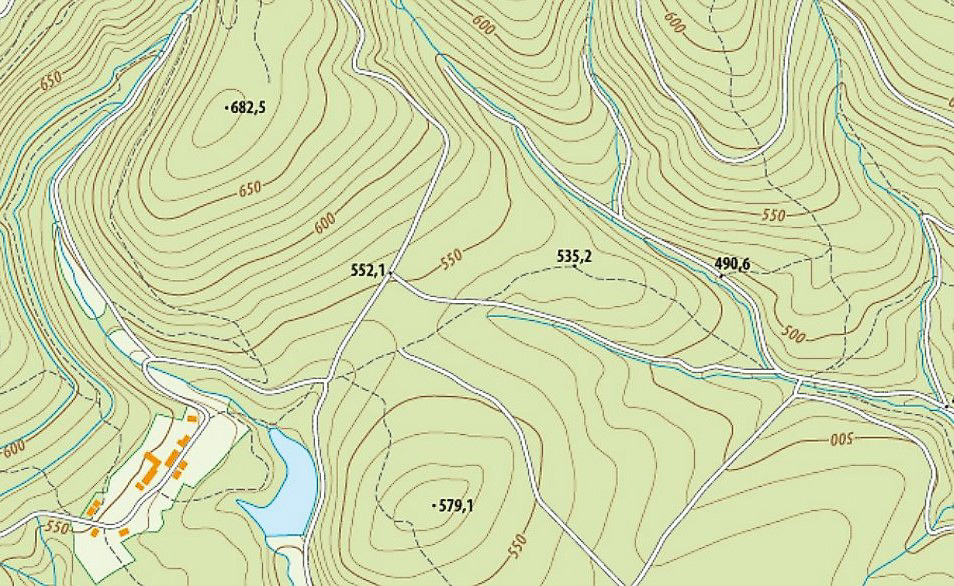

The dramatic change of the prairie habitat at Glacial Heritage Preserve between 1990 and 2017. The dark gray splotches in the 1990 photo are Scot’s broom patches, which are completely absent by 2018.

However, Scot’s broom doesn’t just change prairies by creating shrubland, it also alters the soil by fixing nitrogen and adding woody material into the soil environment. These potential changes to the soil can cause another conundrum – what do we do if Scot’s broom changes prairies even after we remove it? These ‘legacy’ soils could either be maladaptive for our native prairie species, or the other associated European weeds that co-evolved with Scot’s broom in European meadows may be better competitors. For example, species like sheep sorrel, hairy cat’s ear, ox-eye daisy, Yorkshire fog, and sweet vernal grass all readily grow under even the oldest growth Scot’s broom. If these species were able to produce extensive seedbanks under Scot’s broom while outcompeting other native species, they could be equally tenacious and persistent even once we remove Scot’s broom and seed in native prairie species.

Exploring these questions was the basis for a research question I’ve explored for several years. Using the above 1990 map, I set up a natural experiment to see if plant communities that formed under scot’s broom remained different from uninvaded communities even after many years since Scot’s broom removal. What I found was disheartening. Scot’s broom legacy areas were completely stubborn and resistant to our restoration actions, even in prairie locations where we have extensively sown and plugged native prairie species and actively controlled Scot’s broom and other weeds with mowing, fire, and herbicide. Other prairie weeds were little impacted by the presence of Scot’s broom, as we’d expect if they co-evolved in similar habitats in Europe. This was even the case for several cosmopolitan native prairie species that are also native to Europe such as yarrow (Achillea millefolium), self heal (Prunella vulgare) and bluebells (Campanula rotundifolia). In contrast, our regionally endemic prairie species such as white-topped aster (Sericocarpus rigidus) failed to persist or become re-established in legacy soils. For example, western buttercup (Ranunculus occidentalis) growing in legacy soils flower less often, produce fewer fruits, and are shorter in stature than buttercup growing in native prairie. These little studies highlight the big reality that restoration is hard, and being proactive in controlling weeds can be vitally important, because sometimes the consequences are irreversible or nearly so. While we may now have wonderful examples of meadowscapes that would make the characters from a Jane Austen novel blush, we may have lost a unique expression of what makes the South Sound landscape so unique. For a longer presentation on this topic see this talk given at the 2020 Scotch broom symposium.

A sea of hairy cat’s ear, one of the dominant species in prairies that have a legacy of Scot’s broom invasion.