Virtual Puget Sound Birdfest-Post by Dennis Plank

Following up on Adrian’s recent post here, check out the program for the Virtual Puget Sound Birdfest on September 12th and 13th on the Black Hills Audubon Website.

Following up on Adrian’s recent post here, check out the program for the Virtual Puget Sound Birdfest on September 12th and 13th on the Black Hills Audubon Website.

Adrian Wolf has been working on habitat restoration projects for endangered birds for over 25 years. He attributes the inspiration to pursue this profession to his undergraduate professor at the University of California, Irvine. For his Master’s Degree at the Evergreen State College, he climbed up into the forest canopy of old growth Pacific Northwest trees to study the importance of epiphytic resources for birds. Currently, he is a Conservation Biologist with the Center for Natural Lands Management charged with restoring and recovering the imperiled avifauna of prairie oak habitats.

Breeding Birds Winding Down

The 2020 bird breeding season is slowing down, and it has certainly been an unusual one indeed. Since mid-April, the CNLM Avian Conservation Program team has spent countless hours monitoring the birds of our prairie and oak landscapes. Some of the activities have included recording color-band combinations of streaked horned larks, Oregon vesper sparrows and western bluebirds; searching for and monitoring nests; color-banding nestlings; and operating the MAPS bird banding program. This season’s activities were very different from previous years. In years past, the team gathered together on a biweekly basis, commuted together to study sites, and shared office space together for data entry; at the MAPS station, we invited volunteers and encouraged visitors.

However, this has not been possible because of the necessary precautions required under COVID-19. Sure, our lark and sparrow team maintained communications, and still paired up (social-distancing, of course) for field surveys, but it was not quite the same camaraderie typical of previous fieldwork. Despite the socially-different way of doing things, we were steadfast and achieved our deliverables for the year. This speaks to the dedication of our field crew, because each individual often worked alone. Preliminary results suggest that our conservation strategies and actions are working. For example, we estimated that at least 50 breeding pairs of larks were present at JBLM’s McChord Airfield this season – this is more than five times the estimated number when we started monitoring the site intensively in 2013. Similarly, the number of lark pairs present this season at a native prairie training area on JBLM were triple that of the estimated population in 2011. We believe that the conservation action of finding lark nests, and conveying these locations to JBLM site managers, has been a major explanation for the increase in numbers at the three sites over the years. The population of JBLM Oregon vesper sparrows at one prairie site also increased, relative to 2019. We believe that habitat restoration activities at JBLM native prairies has increased and improved the amount of suitable breeding habitat for both species. We thank JBLM Fish and Wildlife and the site managers for adopting pro-active conservation measures to protect these rare grassland birds – clearly, we are seeing the fruits of these efforts.

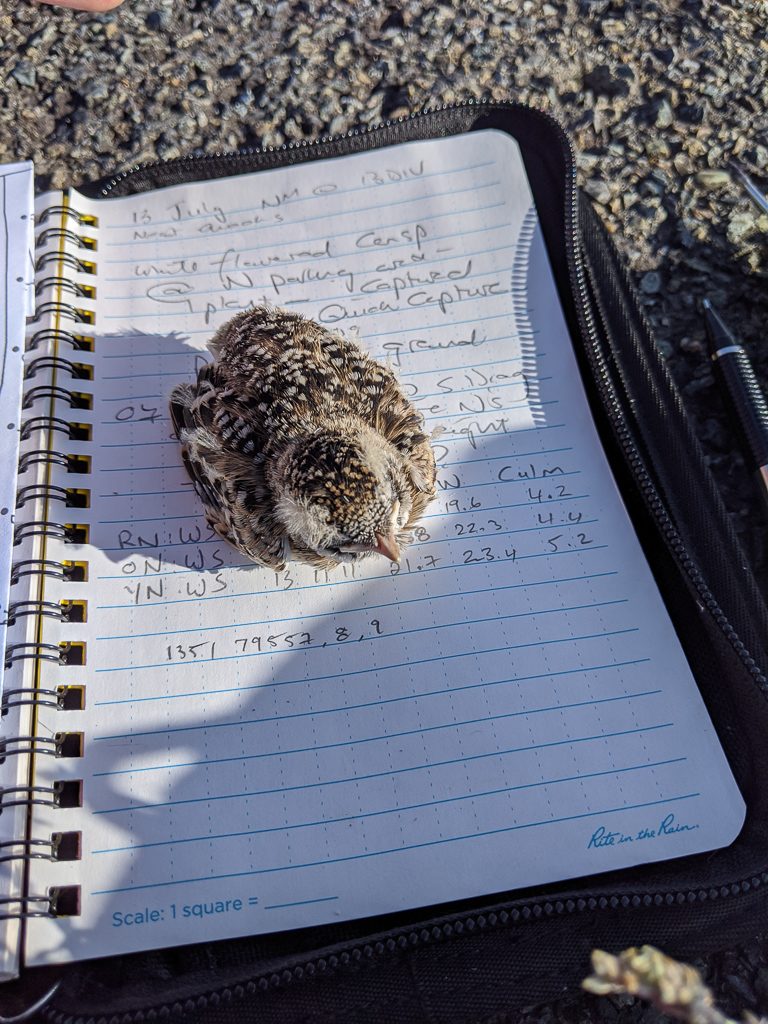

Streaked Horned Lark nestlings. Photo by Adrian Wolf

Streaked Horned Lark nestlings can be identified by the three black dots on their tongues. They young are about 4-5 days after hatching.

Two of more than 290 lark fledglings confirmed from known nests on JBLM this season, photos by Adrian Wolf.

COVID-19 banding ops 2020 – Alicia Beverage measures the tarsus of a lark nestling. Photo by Adrian Wolf.

A lark nestling waits patiently to receive its new colors. Photo by Adrian Wolf.

Over 150 color-banded adults were recorded in the South Puget Sound this season. Photo by Adrian Wolf.

One of more than 60 color-marked lark nestlings this season. Photo by Adrian Wolf.

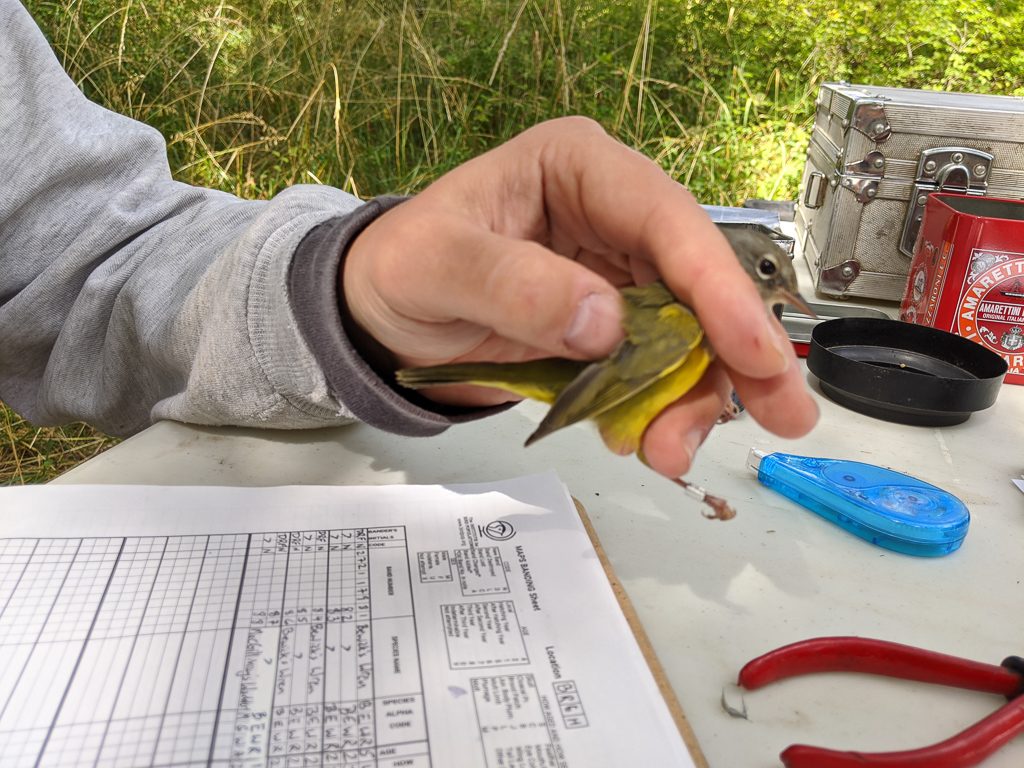

We operated the MAPS station at Glacial Heritage Preserve for the eighth year with a skeleton-crew of four people. We truncated the season and mist-netted birds in the oak riparian bird community on five days (instead of seven), which is still considered a complete season. The capture rates were lower, relative to previous seasons, but included wonderful feathered denizens such as Swainson’s thrush, song sparrow, MacGillivray’s warbler, a hybrid red-breasted/red-naped sapsucker, and cedar waxwings. Hopefully, next year we can once again invite visitors and volunteers to participate in this program that contributes valuable information to a nationwide program of over 400 banding stations.

The MAPS station at Glacial Heritage Preserve is located in an Oregon oak riparian woodland along the Black River. Photo by Adrian Wolf.

A juvenile MacGillvray’s warbler captured at the MAPS station indicates that this species is likely breeding on the preserve. Photo by Adrian Wolf.

Hybrid red-naped x red-breasted sapsucker captured at the Glacial Heritage Preserve MAPS station. Photo by Adrian Wolf.

A cedar waxwing captured and banded at the MAPS station is identified as an adult male by the number of waxy red tips on its secondary feathers, and the length of the yellow edging on its tail feathers. Photo by Adrian Wolf.

I am Forrest Edelman, I work for the Center for Natural Lands Management within the Nursery Department and perform the functions of a seed processor.

Seed Cleaning

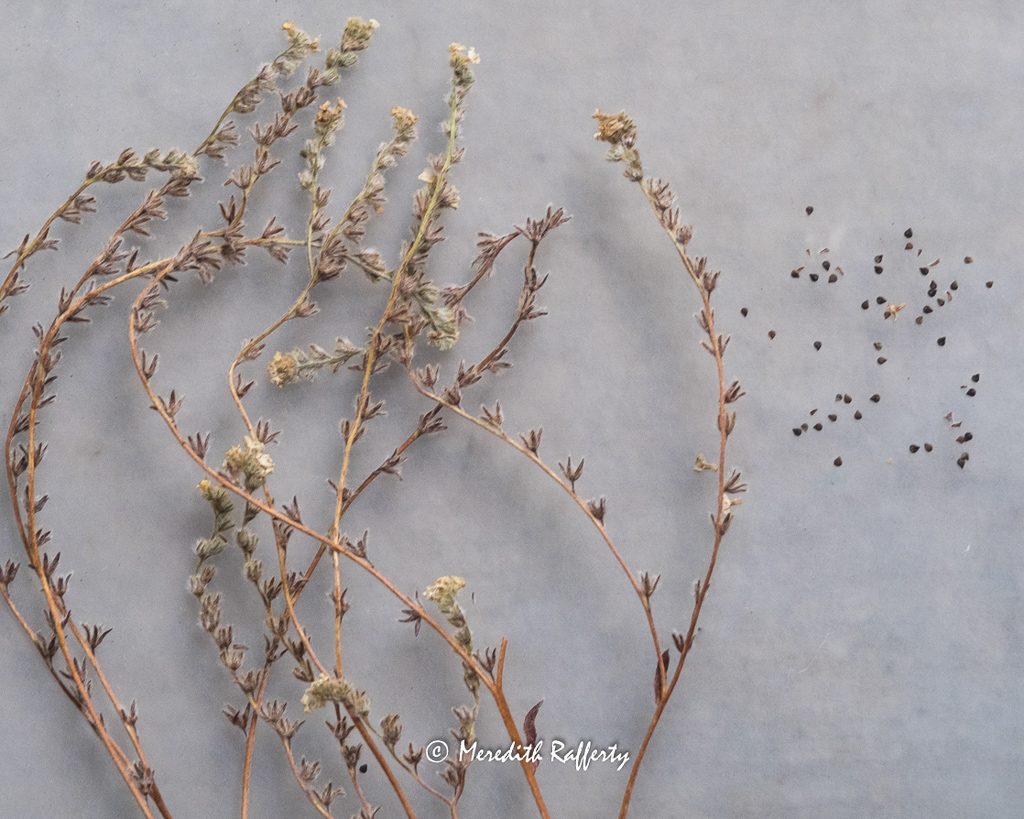

After flowers have finished and seed pods have ripened, the plant material is harvested and laid out to dry in a drying shed. When the material is good and dry it is binned up and goes to the seed processing shop for the separation of seed from the rest of the material. The species being processing here is Primula pulchellum or the Few Flowered Shooting Star.

Raw Material, photo by Forrest Edelman.

Most of the seed falls out of the open cup style pod during the drying processing, for those that are caught in the pods and between the material, they will be sent through a hammer mill to dislodge the remaining seed.

Hammer Mill, photo by Forrest Edelman.

The hammer mill is a threshing type machine which uses a motor to spin and swing nylon rectangles which abrade the material in a closed metal compartment, thereby mechanically dislodging seed from inert material.

Feeding the Mill, photo by Forrest Edelman.

The material is fed down a metal chute through a metal gate into the threshing compartment. All of the seeds and plant material will be threshed and dropped in a single steam, to be screened down next. In short; when the machine is spinning, material is fed into the machine and it lightly chews it up and spits the mess into a bin to be moved on to the next step.

Output from the mill, photo by Forrest Edelman.

Removing most of the large chaff with a brass sieve is the next step. It consists of dropping handfuls of material into the sieve and shaking the smaller pieces of plant material and seeds through then removing empty pods, sticks, and other large chaff.

After the screening process, photo by Forrest Edelman.

Afterward the material should be more even in size and drastically reduced in bulk, which makes it easier to load into the next machine, an office clipper.

An office clipper is an air screener separator machine, it allows seeds to drop through a larger top screen and get rid of more chaff.

Clipper and Bins, photo by Forrest Edelman.

Back view of Clipper, photo by Forrest Edelman.

The lower screen allows for fine chaff and dust to fall through but seeds and material of similar size roll off the lower screen.

Clipper Screens, photo by Forrest Edelman.

Loading the Clipper, photo by Forrest Edelman.

This in between size material falls into a compartment which has air blowing up through it. Seeds are generally heavier than dried plant material fragments of the same size, so the air stream will winnow away the remaining chaff and drop good seed into a bin. After a couple of runs though this machine the final product is seeds.

Close-up of the final product-nearly pure Primula pulchellum seeds, photo by Forrest Edelman.

This is just one method for one species. There are many ways to reach a final product for each of the 80 or so plant species processed every year.

Dennis has been getting his knees muddy and his back sore pulling Scot’s Broom on the South Sound Prairies since 1998. In 2004, when the volunteers started managing Prairie Appreciation Day, he made the mistake of sending an email asking for “lessons learned” and got elected president of Friends of Puget Prairies-a title he appropriately renamed as “Chief Cat Herder”. He has now turned that over to Gail Trotter. Along the way, he has worked with a large number of very knowledgeable people and picked up a few things about the prairie ecosystem. He loves to photograph birds and flowers.

Tansy Season

A personal perspective

My wife, Michelle, eyeing a patch of Tansy earlier this year. Photo by Dennis Plank

July and August have become a very special time of year for me because of this plant. On the 6th of July my computer reminds me that “Tansy season is approaching”, a message that was quite unnecessary this year as I had already seen plants blooming on the access road to Thurston County’s Glacial Heritage Nature Preserve (hereafter Glacial) and had the pleasure of removing them.

About 14 years ago, one of our stalwart volunteers mentioned to my wife (an avid horseman) that he’d seen a lot of Tansy Ragwort on Glacial and shouldn’t she, as a horse person, do something about such a pernicious stock poison? The guilt trip worked, and she started single-handedly working on it. The first couple of years she collected the entire plants, bagged them and took them to the transfer station. If memory serves me correctly (it does so less and less as I get older), she had in excess of 40 garbage bags that first year and a similar amount the next. At the time, I was still working in Seattle and just down here on the weekends, so I think it was the third year when I started helping her on weekends and it wasn’t until I retired in 2012 that I started working it in earnest. For several years, it occupied three or four days a week in July and August. About the time we were burning out, the Center for Natural Lands Management assigned Angela winter as permanent volunteer coordinator, and she was more than willing to work at controlling Tansy on Glacial heritage and other preserves that they manage. The last three summers, we were surprised by a significant decline in the amount of this plant, which we attributed to the extremely dry conditions. Unfortunately, this year it returned with a vengeance.

Somewhere in there we realized that we really didn’t need to be taking the whole plant to the transfer station, just the flower heads. The native animals weren’t going to eat the bodies of the plants with so much else available. That reduced the number of bags to a small fraction of what they had been and was a great relief when working the interior parts of the preserve where it was a long way back to the road.

A morning’s haul of tansy blooms. Photo by Dennis Plank

For me this two month period has become a time of hard work, a little frustration, a little satisfaction and a whole lot of joy. The hard work part is obvious. The frustration comes because at times (like this year when we’re having a bad year for weeds in general and Tansy in particular) it seems like we’ll never get anywhere. The satisfaction comes because I can look back at what it was like when I first started helping and see that there really has been an improvement. The joy comes because I have a wonderful excuse to be out on the prairie early in the morning, alone with the flowers, birds and bugs, doing something that I consider very worthwhile.

A very healthy specimen. Photo by Dennis Plank

So what’s with Tansy Ragwort?

Tansy Ragwort, Senecio jacobaea, is a plant in the sunflower family native to Europe, western Asia and northern Africa and since spread by us to nearly every corner of the world. Like many composites, it is extremely successful. A single plant can produce 150,000 seeds and they can either sprout the following year or lie dormant for at least 10 years if conditions aren’t right. Additionally, the roots, which penetrate up to one foot in the ground have many adventitious buds that can sprout new plants if the parent is uprooted. The plant is listed as a biennial, but a large percentage of plants act as if they were perennials, particularly if they are cut or otherwise disturbed. In good years for the plant (bad years for us) it can form very large, nearly mono-cultural patches in disturbed soils. This year’s outbreak is also in Oregon. The image below was taken in Clackamas county.

A Tansy field in Clackamas County Oregon earlier this year. Photo by Samuel Leininger WeedWise Manager Clackamas Soil & Water Conservation District

If it were just a prolific weed, we might treat it like we do Oxeye Daisy or Hairy Cat’s Ear and pretty much live with it. However, all parts of this plant contain Pyrrolizidine alkaloids that accumulate in the liver and are poisonous to deer, horses, cattle and goats, but apparently not to sheep which are used in New Zealand as a control for the plant. Most animals will not eat the plant if there is anything else. I’ve seen people’s horse pastures in this county completely devoid of all vegetation except clumps of this plant four or five feet tall that are completely undisturbed. However, if it’s in a field that is mowed for hay, the plant will still contain the toxins after drying and animals will inadvertently ingest it. At various times, there have been outbreaks of sickness and death in cattle and or horses in various parts of the world that achieved their own disease names (Stomach Staggers in Wales, Pictou disease in Nova Scotia, in South Africa Molteno disease for horses and Dunziekte for horses, and in Norway Sirasyke) before someone figured out that they were just Tansy poisoning from tainted hay. And it’s not something that’s over. I see people with small hay fields and Tansy growing in them that are being mowed and baled in this county. Unless someone is going out the morning they mow and pulling the Tansy, it’s getting in the hay. Since the toxins are in the flowers and pollen as well, they also taint honey from bees that use the plant in any quantity and can actually make the honey carcinogenic.

It seems as if people have a fascination with toxic plants and they become a part of folklore and folk medicine. Tansy Ragwort is no exception to this. In Britain and other areas it was used extensively in folk medicine where an ointment was made by boiling it in hog grease and applied to arms legs and hips for joint pain. One source I ran across quotes: “A poultice made of the fresh leaves and applied externally two or three times in succession ‘will cure, if ever so violent, the old ache in the hucklebone known as sciatica’.” It was also used as a mouthwash for canker sores and ulcers of the throat. The wide use and knowledge of the herb led to lots of interesting colloquial names such as: St. James his wort, stagger-wort, staner-wort, ragwort, ragweed, curly doddies, stinking nanny (have I mentioned that it smells), dog standard, cankerwort, stavewort, kettle dock, felonweed, fairies horse, stinking willy, mares fart, cushag, fleawort, seggrum, jacoby, and yellow top. In places, it also became associated with witchcraft and references are made to witches riding stems of it instead of brooms.

The good side of Tansy Ragwort

On the South Puget Sound Prairies, most of the more prolifically flowering plants have gone to seed by the middle to end of July and nectar sources for late season butterflies and other pollinators are in short supply. People doing butterfly surveys say that this time of year the best place to find butterflies is the patches of Tansy. For this reason, some of the state agencies have decided to control it when it might affect neighbors, but leave it to the bio-controls when it’s on the interior of their properties.

Zerene fritillaries nectaring on Tansy Ragwort at Mima Mounds Natural Area, Photo by Brad Gill.

Tansy is also heavily used by Crab Spiders. These little beauties lie in wait on the flower heads where their color blends in very well and ambush pollinators that come in to nectar on the blossoms.

Crab Spider with Prey, photo by Dennis Plank

This crab spider didn’t get the dress code message, photo by Dennis Plank

Many other insects also use Tansy on occasion, such as this Great Golden Digger Wasp.

Great Golden Digger Wasp, photo by Dennis Plank

Identification and Control of Tansy Ragwort

Like most plants, once you get the image in your head, it’s pretty easy to separate this plant from just about anything else. The closest look-alike is Common Tansy, which is easily mistaken driving 50 mph and seeing it in the ditches. On closer inspection, the single stems with flat clusters 3-4 inches in diameter and the absence of ray flowers on the composite blooms makes the Common Tansy easy to distinguish.

Common Tansy on a roadside in south Thurston County, Washington, photo by Dennis Plank.

St John’s Wort would never be mistaken for Tansy Ragwort when seen close up, but when we’re on the prairie trying to find tansy, we are often looking several hundred yards away and the colors of the blooms are quite similar. The key is the shape of the bloom head. Tansy looks almost flat at a distance, while St John’s Wort tends to be more rounded and less dense. I‘ve traipsed quite a ways only to realize I was after the wrong weed. We had one St. John’s wort that fooled us for most of the season a few years ago. I finally got frustrated and pulled it. It may seem odd to take binoculars to pull weeds, but they save a lot of walking. Even a yellowing fern leaf turned the right way can look like a Tansy bloom head when it’s a couple of hundred yards away.

St. John’s Wort, photo courtesy of Washington State Noxious Weed Control Board

Common Groundsel is another plant that somewhat resembles Tansy Ragwort in the leaf structure, but when it blooms the flowers are very small and never open very far. It is an annual and seems to have great seed life as it is common to have a flush of it the first year or two after a fire. The Center for Natural Lands Management used to use Americorps volunteers as their volunteer coordinators and we had one, who shall remain nameless, who insisted we rip out a huge patch of Groundel on a rainy, ugly day under the mistaken impression that it was Tansy Ragwort. I’m not sure I’ve forgiven her yet.

Common Groundsel, photo courtesy of Washington State Noxious Weed Control Board

The final look-alike is only a problem when the plants are very small. That’s the Oxeye Daisy. The young rosettes of the species do bear a superficial resemblance, but it doesn’t take very much practice to start distinguishing the two.

Tansy and Oxeye Daisy rosettes side by side. Note the purple stems on the Tansy. Photo by Dennis Plank

Three bio-controls have been introduced in the Western US since 1959 to combat infestations of Tansy Ragwort. The first of these is the Cinnabar Moth first introduced in California in 1959. It is well established in Washington and Oregon. The moth lays its eggs on the underside of rosette leaves and the larvae eat all above ground parts of the plant, sometimes causing sufficient damage to kill it, though more often just setting it back for the season. The larvae seem particularly fond of the blossoms. Unfortunately, like most bio-controls, the population of the moths depends on the population of the Tansy, so it is most effective when there are huge infestations of the weed. When the infestation is patchy, we see relatively few plants with Cinnabar larvae (often called Tansy Tigers for their coloration) on them. Also, unless the numbers of larvae are extremely large, our experience has been that the denuded stems left by the Tigers will releaf and rebud later in the season and often produce late season flowers and seeds just when we’re very tired of looking for the plant and have let down our guard.

One of the down sides of the Cinnabar moth is that it will use a couple of native plants for as hosts for the larvae including Packera Macounii, commonly known as Siskiyou Mountain Ragwort, Macoun’s Groundsel, or Puget Groundsel.

Cinnabar Moth Larva (aka Tansy tiger) hard at work, photo by Dennis Plank.

The second of the bio-controls is the Ragwort Seed Fly (Botanophila seneciella) introduced in California in 1966 and present throughout the Pacific Northwest. This fly lays its eggs on the flower buds and the larvae dig into the bud and set up housekeeping near the base of the bud where they happily eat the entire flower. I just noticed these this year, though I’m sure they’ve been around before. They are detectable by a brown spot in the middle of the disc flowers often with some bubbles on it. The spot increases in size until the entire disc is brown and the ray flowers disappear. Unfortunately, studies have shown that only 10-40% of the flowers are predated by the bud fly larvae.

Tansy Seed Fly Larva. Microscope photo taken by teasing away the outer parts of the seed head. Photo by Dennis Plank.

Flower head predated by Seed Fly Larvae, photo by Dennis Plank.

The third bio-control is the Ragwort Flea Beetle, Longitarsus jacobaeae. This species is primarily effective at the rosette stage where the larva attack the roots and the adults eat the leaves producing an effect called “shot holing” where the leaves are heavily perforated with BB size holes. Some people consider this the most effective of the bio-controls since the larvae attack the root crown over the winter and early spring and a late spring dry stretch can actually kill the weakened plants. I’m sure we have this beetle, but I’ve yet to identify it on a plant.

Mowing and cutting are not effective means of control as they essentially move the life cycle of the tansy into the perennial mode. One local land manager, has a practice of just breaking over the bloom stem, leaving it attached. Our experience with this technique is that unless it is done perfectly, it doesn’t kill the flowers and they still go to seed. Also the plant can continue to put out new flower heads after the first is broken.

Tansy plant that had the heads broken over and left attached earlier in the season. Note the mature seed head in the yellow circle. Photo by Dennis Plank.

There are herbicides that are considered effective, though they need to be used with care. Apparently they make the plant more palatable, so for the first few weeks after application it’s necessary to keep the grazers away from those plants as the poisons don’t go away.

As mentioned above, New Zealand has had good success using sheep to graze infected areas in the early season, so that could be a viable approach.

An accidental discovery happened at the CNLM Mima Creek preserve a few miles south of Glacial Heritage. This is an old farm with low lying pastures pretty much in the Black River flood plain. Several years ago, it had a very bad Tansy Ragwort infestation and volunteers and staff from CNLM put an enormous number of hours into just topping the plants as an emergency measure to keep seed from getting into neighboring hay fields. Then the beaver moved in and raised the water table a bit and suddenly there was no more Tansy. Hopefully, they’ll keep up the good work. Since it is being managed for the Oregon Spotted Frog (which has found its way there), the raised water table is a good thing.

The last control method, and the one we’ve been using with some success (though this year feels like a major setback), is simply digging the plant out with as much of the root as we can get, bagging the flower heads, and leaving the stem and leaf on the prairie. It’s crude, but eventually seems to do the trick, though there are patches with deep roots that do keep coming back.

Dead Tansy in the Middle of the Road (heads were removed and bagged after taking this photo). Photo by Dennis Plank

Happy Tansy Hunting.

References

USDA NRCS Plant Guide on Tansy Ragwort

World of Weeds: Tansy Ragwort

Washington State Noxious Weed Control Board Brochure

Uses of Tansy Ragwort in Magic

Art Cornwall: Tansy in Witchcraft

Botanical.com (A modern herbal) on Tansy Ragwort

The Herbal Supplement Resource on Tansy Ragwort

Article on Tansy Contamination of Honey

Anika Goldner is the current Volunteer and Education AmeriCorps at CNLM. This season she’s been working with the Wild Seed Collection Volunteers and at the CNLM seed farm.

Meredith Rafferty is a volunteer seed collector and photographer.

In partnership with CNLM’s seed farm a wild seed collection team ventures into the prairies every spring and summer to gather seeds and scout for rare plant populations. The collected seeds are brought back to the farm and cleaned. Some of them go directly to plug production, some are planted at the farm to add genetic diversity to the crops already growing there, and some are for establishing new seed banks.

Rainier from the Prairies. Photo by Meredith Rafferty

At the farm seeds are collected from the same beds and rows of plants year after year, while these seeds are not babied the way one may tend and fertilize a crop of tomatoes, their lives at the farm are easier than life in the wild. Weeded and occasionally watered, the beds of plants don’t have to compete with the weeds that would shade them out, take their nutrients, or release hormones to suppress their growth. Collecting from the farm year after year to reseed restoration areas would be providing seeds that may not be the most adapted to thrive in the wild. This is why collecting wild seeds to add genetic diversity to the crops growing at the farm is required.

Plagiobothrys figuratus, Fragrant Popcorn Flower seeds. Photo by Meredith Rafferty.

When collecting seeds from wild populations we need to harvest ethically.

We do not want to take seeds in a way that will damage the presence of the plants on the prairies. Some plants are easy to not over-harvest; violets are often seen with seedpods at all stages of ripeness. A healthy violet plant might have a few stems that have already released seeds, a few blooming flowers and a few pods that are mature but have not yet burst. With these plants we can take the mature pods knowing that this plant has already distributed some seeds to the prairie and has more to contribute.

Bug inside a seedpod. Photo by Meredith Rafferty

Other plants require the harvesters to collect with more intention. When we collect from rare plant populations, especially the ones that hold onto their seeds, getting a count on the number of plants seen and collecting only 10% of the population is required. One collection day we spent the entire day getting a count on all the golden paintbrush plants, including how many flowering stems and seed pods were seen on the entire prairie. On this day we didn’t harvest any seeds because we need to make sure we can harvest without impacting the health of the population. After analysis, a group of people may be able to use the numbers and the GPS location of all the plants to collect a small amount of seeds from the most densely populated areas.

Golden Paintbrush. Photo by Meredith Rafferty

Even on the days when only a small amount of seed is collected, we are still contributing to the growth of plant populations. When I walk across the fields to get from data point to data point I hold my clippers and cut down all the tansy that comes into my path. When I snooded a lupine, small seeds were flung into the air some were caught in the cuffs of my pants. I discovered them at lunch and placed them into a small patch of dirt on the side of the road. All of the seed collectors do these little acts of prairie love. Some pull up invasive plants, some decide that the small amount of seed they’ve collected isn’t enough to bring back and dump it back out into the dirt, moving native plants a little bit father than the plants would have managed themselves. Even just walking through the prairie we can hear the camas rattle as we knock them over and they release seeds.

Talyor’s Checkerspot on a balsamroot flower. Photo by Meredith Rafferty

Senescence

Dennis has been getting his knees muddy and his back sore pulling Scot’s Broom on the South Sound Prairies since 1998. In 2004, when the volunteers started managing Prairie Appreciation Day, he made the mistake of sending an email asking for “lessons learned” and got elected president of Friends of Puget Prairies-a title he appropriately renamed as “Chief Cat Herder”. He has now turned that over to Gail Trotter. Along the way, he has worked with a large number of very knowledgeable people and picked up a few things about the prairie ecosystem. He loves to photograph birds and flowers.

This time of year the prairies remind me of an aging genius. Most of its productive life is behind it, stored in seeds. Waiting. Waiting for just the right conditions to flourish and create yet another generation. But here and there, buried in the uniform gold of the grasses, are sparks of life still perpetuating the current generation and bringing great beauty in the process.

Panorama view of Glacial Heritage, photo by Dennis Plank

Of the natives, the most obvious is Canada Goldenrod, Solidago canadensis, growing in isolated patches on the prairies, predominantly on roadsides, but here and there on the open prairie. When I first started volunteering here, there was none of this beautiful plant on Glacial Heritage, nor do I recall seeing any on Mima Mounds. Now the clumps of this plant are fairly common and it is a lovely addition to the late summer prairie as well as an excellent late season nectar source.

Canada Goldenrod on Glacial Heritage Preserve, photo by Dennis Plank

Another goldenrod, Solidago missouriensis, is also blooming this time of year and in favorable situations may be visible above the grasses. It tends to be found as individual plants, though more concentrated in some areas. I tend to find it in areas of slightly better soil and a bit more moisture, though there is little of that on the prairie this time of year. I describe our soil as having all the water retention of a sieve since it is basically a gravel bar with a very thin layer of organic soil on the top.

Solidago missouriensis, Missouri Goldenrod, photo by Dennis Plank

Continuing with the composites, Western Pearly Everlasting, Anaphalis margaritacea, is also in bloom, though small white heads are relatively inconspicuous and it tends not to rise above the grasses, particularly the invasive pasture grasses.

Pearly Everlasting taken in a neighbors yard, photo by Dennis Plank

A close-up look at the Pearly Everlasting blossoms, photo by Dennis Plank

A similarly inconspicuous white flower is Pussytoes, Antennaria howellii. This species tends to be even shorter than the Pearly Everlasting and while found in loose groups does not form a bunch like the Pearly Everlasting that’s illustrated above.

Pussytoes, photo by Dennis Plank

Spreading Dogbane, Apocynum androsaemifolium, is also supposed to be blooming this time of year, but I haven’t been able to find one with blooms yet. This is a spreading woody plant that can form quite large patches and is a very important nectar source this time of year.

Another plant still blooming is Scouler’s Catchfly, also known as Simple Catchfly or Simple Campion, Silene scouleri. I’ve also heard it called Stickyweed because it does stick to your fingers. Like most of the plants this time of year, it’s not very showy, so you have to look closely to appreciate it.

Scouler’s Catchfly, photo by Dennis Plank

A close-up of the blossoms of Scouler’s Catchfly, Photo by Dennis Plank

Of the earlier plants, Showy Fleabane is still in bloom here and there, though it’s starting to look pretty ragged. The Harebell is still blooming, though in lesser numbers and it will continue well into the fall. On well vegetated mounds, one can still find the prairie violet, Viola adunca, blooming as well.

Among the non-natives, even the Oxeye Daisy and the St. John’s Wort have almost finished, but a new and unwelcome star has risen above the prairie and that is Tansy Ragwort. Like many plants this year, native and non-native, this one has done extremely well. The last few years there wasn’t much of it, but this year t is very abundant. But more on this plant in a later post. Hairy Cat’s Ear, Hypochaeris radicata, is also still blooming and never seems to stop, though I know it will by fall.

Tansy Ragwort, photo by Dennis Plank

The birds are pretty much done making babies for this year. Now it’s time for them to learn how to be adults. In my last few visits to Glacial Heritage, I’ve seen hundreds of swallows on the power lines and fences along the entrance road, a flock of 10 Western Meadowlarks (probably the offspring of a single male and his two mates), and a flock of six American Kestrels-again probably a family group. Around our own property, the Western Bluebirds have fledged their second crop of youngsters with the help of some of the first brood and now have them secreted somewhere until they’re old enough to bring back (probably within the week). They have been known to raise three broods, and that’s a possibility this year as the relatively wet spring produced a lot of foliage and that’s been followed by lots of grasshoppers which make excellent Bluebird food. We have a large number of juvenile American Goldfinches coming to the feeders. They learn to feed themselves quickly, but until they do they have a plaintive cry that is easily rendered as “feed me”. Usually, they raise two sets of young in a season, with the male taking over rearing after the first batch fledges and the female taking up with another male (usually an inexperienced first year bird) for the second crop. We saw a female feeding young today, which is a good sign that the second crop of this species is starting to fledge.

Juvenile American Goldfinch, photo by Dennis Plank

Another sure sign of this time of summer is that the Yellowjackets are starting to make their presence felt. I was digging out Tansy on Glacial Heritage recently and ran afoul of a nest, so keep your ears open for them.

Michelle Blanchard is a long time prairie volunteer and self-described “muddy boots biologist”. She learned her bird banding at Ft. Hood in Texas where she volunteered with The Nature Conservancy on a very successful Golden-cheeked Warbler recovery program.

Editor’s Note:

I was out at Glacial Heritage pulling Scotch Broom and enjoying the wonderful flowers on June 2nd this year. Meadowlarks were singing from all sides and the females were giving their “telephone” calls, when suddenly the air seemed filled with male Meadowlarks chasing one another around the area and singing at the top of their lungs. While it was actually only four or five birds, it was an amazing experience. Even more amazing, a short while later, I heard a male singing in a very different way. It was soft and a bit more melodious and the song went on and on. I told Michelle about it and she thinks it’s the male just singing to its mates telling them that he’s there and all’s right in the meadowlarks world. I thought then that it was so wonderful that we were able to restore a place where Meadowlarks can sing. It made me very happy to have Michelle write this post.

P.S. It’s about as hard to photograph these birds as it is to trap them, so the images in this post are from a variety of locations where I got lucky.

-Dennis Plank

Western Meadowlarks at Glacial Heritage

If there is an iconic bird of the prairie, it can only be the Western Meadowlark.

Sturnella neglecta is an icterid, also known as ‘blackbirds’.

Great-tailed Grackle from the Texas Coast, Photo by Dennis Plank

Altamira Oriole from the Rio Grande border of Texas, photo by Dennis Plank

Most-not all, (for the orioles are icterids, too) icterids are somberly clad in blacks and browns. The meadowlarks, though, have a brilliant yellow breast, emblazoned with a black chevron at the base of the throat. If that weren’t enough, they are singers, too, something icterids are not known for.

Western Meadowlark at Glacial Heritage Preserve, photo by Dennis Plank

Our Western meadowlark is almost indistinguishable from the Eastern meadowlark, but the moment you hear the two sing, you know that the Western is by far the better singer. Here are the clips from the CD accompanying “Stokes Field Guide to the Birds of North America”, Little, Brown and Company, 2010.

As well, the Western is much fussier about his habitat. All meadowlarks are obligate grassland species, but the Western demands just the right height of grass-not too tall and not too short. It’s why you’ll never see a meadowlark on a golf course.

I was stationed at Ft. Lewis in the late 80’s and early 90’s. Being that my specialty was tanks, I spent a great deal of time in ‘the field’ and often heard meadowlarks. I began to appreciate them for their singing. Eastern Meadowlarks have only one or two songs. Westerns have a much larger repertoire of several songs, the number increasing with age and dominance.

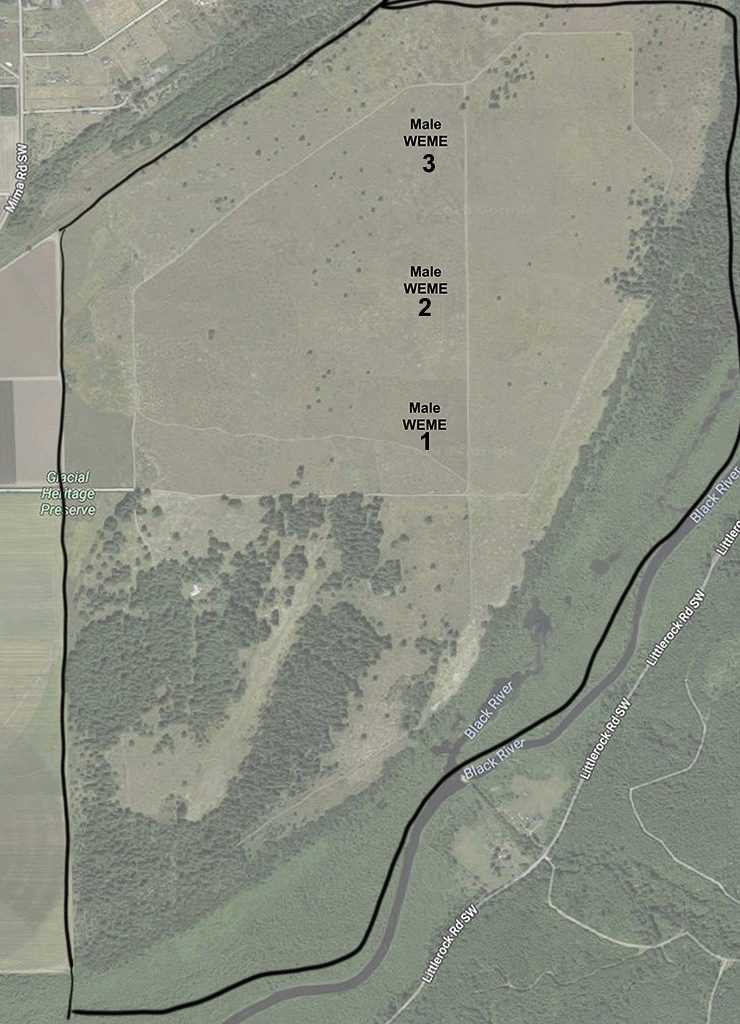

I began volunteering on Glacial Heritage in the late 90’s. Considering its size, it was worrisome and depressing that I counted only three singing males on all of Glacial.

The three territories identified at Glacial Heritage. Map courtesy of Google Maps

This I attributed to the fact that GH, at the time, was a vast expanse of Scotch broom and Douglas firs. In a treeless prairie, meadowlarks will sing on the ground, but Glacial Heritage had plenty of invasive Douglas firs from the tops of which they’d sing. Their territories were small due to very little suitable grassland, not enough to support any sizable population of meadowlarks. It appeared that the tiny resident population was hanging on by a thread. In fact, I was showing a person around the preserve one time, and one of the three males sang. I said, ‘Oh, there’s one of my meadowlarks.” Her voice dripping scorn, she said, “No, it’s not, there’s no meadowlarks west of the Cascades.”

Oh. I guess I have a really vivid imagination.

Western Meadowlark singing from the ground. Photo taken at the National Bison Range in Montana by Dennis Plank

The more I learned about them, the more I grew enamored with meadowlarks.

I mapped out where the meadowlarks were, and got to know them by their songs. I learned to tell who each male was by where and what he was singing. They impressed me with their intelligence. But, alas for this birder, they’re highly suspicious of humans. If she knows her nest has been discovered, the female will abandon it immediately. Meadowlarks are unwilling to tolerate close human proximity or even observation. One time I had my binoculars focused on a female that was perched atop a small shrub. She held a wriggling grasshopper, telling me she was feeding hatchlings. Would she show me where her nest was? It became a grueling duel-my increasingly tiring arms, and her refusal to move an inch while under my observation. Finally, after an eternity, I blinked-and she was gone.

What would happen, I wondered, when we had Glacial at least partially restored to open grassland? Would the meadowlarks respond? Would they be able to survive the lengthy time it would take to restore Glacial?

I had to know.

I possess a Master Bander’s Permit. I developed a research plan to identify individual meadowlarks and applied to the Bird Banding Lab for a string of bands for Western Meadowlarks. Florence Sohenlien, the BBL’s band manager at the time, approved my study and sent me a string with the warning: “You’re the fourth person I’ve sent this string of meadowlark bands to. It’s never been broached. Good luck.”

Western Meadowlark in full glory at Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge, photo by Dennis Plank

She was right. My approval to band Western Meadowlarks was for three years. In those three years, I got up before dawn to set up nets. I deployed walk-in traps, baited with live grasshoppers. I created and painted a meadowlark decoy out of Play Dough. It was hideously ugly but I hoped the birds wouldn’t mind. I bought (at nosebleed prices from Cornell) a CD of W. Meadowlark calls, along with the game caller to play it. I’d set up my nets in areas I knew males held as territory, and would hear them warning their mates of my presence.

The resident male always responded to the CD. He’d swoop in, looking for the brazen interloper singing on HIS territory. He’d perch on the net poles and sing. Walk the top panel of the net like a tightrope, looking, looking. He’d stand atop the walk-in trap. Circle overhead, sounding his battle cry, daring the intruder to come out from hiding (or was he mocking the decoy, saying, gads, you’re ugly!) But actually fly into my nets? Or to take the bait in the traps? Nope. Not once. Not in three years.

What was I doing wrong? Was it my method? My set up? I contacted every bander in the US and Canada who had banded meadowlarks and asked, how did you catch them? Was it your net configuration? CD calls? Traps, bait, time of day? The answer was always “dumb luck”. I didn’t have luck of any level, dumb or smart. I returned the string of bands after three years, not once ever having been broached.

Federal bird bands managed and distributed by Craig “Tut” Tuthill, Photo taken Thursday, September 14, 2017. Unidentified Photographer. He didn’t have to return them all.

However, despite my never banding a meadowlark, I can say that my theory was proven correct. With the restoration of their preferred habitat, especially through controlled burns, by removing scotch broom and trees, the population of meadowlarks has grown. I can no longer count how many males I hear singing because they’re everywhere. In the spring and summer, the prairie rings to their songs. In the fall and winter, you’ll see them in large flocks, arrowing over their beloved grassland.

Glacial Heritage’s prairie icon has returned. And he likes what he sees.

Glacial Heritage panorama taken from the northwestern edge of the WEME 3 territory on May 9th, 2020. Photo by Dennis Plank