Species interactions in a prairie butterfly: Puget blues, ants, and nectar plants. Post by Rachael Bonoan, Kelsey King and Hanna Brush, Photos by Rachael Bonoan.

Rachael Bonoan (rachael.bonoan@tufts.edu): Rachael is a post-doctoral researcher at both Washington State University and Tufts University. Rachael spends the Puget blue season searching for caterpillars and chasing butterflies in the South Puget Sound and the rest of the year in the lab and analyzing data at Tufts University in the Boston Area. This fall, Rachael will be joining Providence College (Providence, RI) as Assistant Professor of Biology where her lab will study nutritional ecology of bees and frosted elfins.

Kelsey King (kelsey.king@wsu.edu): Kelsey is a PhD student at Washington State University. For her dissertation, Kelsey is investigating the potential of resource mismatches between butterflies and nectar plants, as well as demonstrating the ways nectar resources can impact population dynamics.

Hanna Brush (maria.brush@tufts.edu): Hanna is a Portland, OR native and an undergraduate student at Tufts University who has been helping Rachael study Puget blue butterflies since 2018. This season, Hanna will be investigating nectaring preferences and behavior of Puget blue butterflies for her senior honors thesis.

Species interactions in a prairie butterfly: Puget blues, ants, and nectar plants

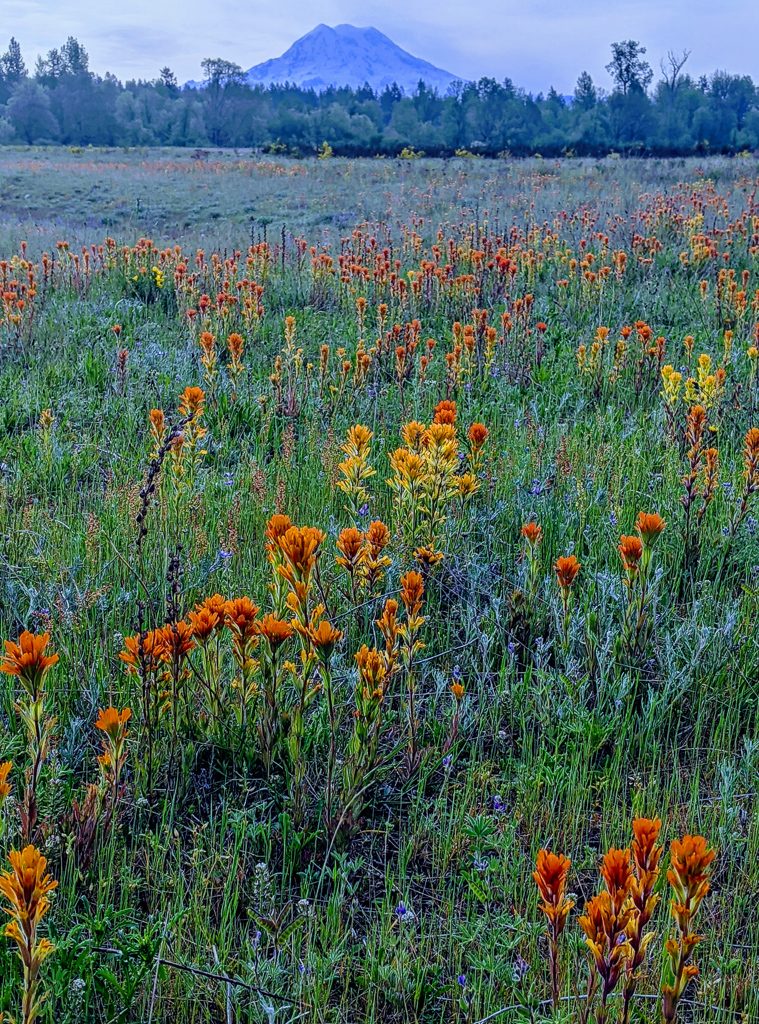

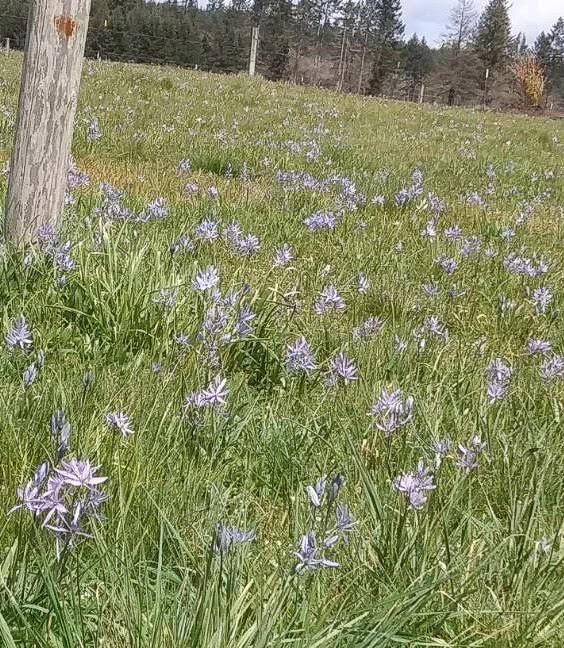

This time of year, Puget blue butterflies (Icaricia icarioides blackmorei) have just emerged from their underground pupation at our field site, Johnson Prairie (Joint Base Lewis-McChord). Soon, hundreds of Puget blues will be flitting around the prairie, laying eggs on their host plant, sickle-keeled lupine (Lupinus albicaulis). When it comes to preserving habitat for host plant specialists, biologists rightfully focus on preserving the host plant. This focus, however, may be missing other key interactions in the butterfly’s biology.

Sickle-keeled lupine (Lupinus albicaulis) and other wildflowers on Johnson Prairie. Photo by Rachael Bonoan

Puget blue female with her abdomen curled to lay an egg on the underside of this lupine leaf. Photo by Rachael Bonoan

Caterpillars and ants

Soft and squishy, Puget blue caterpillars are vulnerable to predators such as carnivorous wasps and spiders. When threatened, Puget blue caterpillars signal for help via scent, sound, or both. In response, nearby ants come marching. The ants protect the caterpillar by patrolling the plant, physically standing on top of the caterpillar and in some systems, the ants carry the caterpillar underground to their nest. Once the threat has passed, the caterpillar uses a specialized organ to secrete a tiny sugar droplet as a “thank you” to the ants.

Ant receiving a sugar reward from a fourth instar Puget blue caterpillar. Photo by Rachael Bonoan

This ant-caterpillar interaction is part of the life cycle of many butterflies in the Lycaenid family. While very little is known about this interaction in Puget blues, the ants are often beneficial for caterpillar survival. For example, silvery blues (Glaucopsyche lygdamus) tended by ants showed 45 – 84% less parasitism than untended caterpillars; experimental exclusion of ants from Reakirt’s blues (Hemiargus isola) doubled caterpillar mortality; and in the lab, Miami blues (Cyclargus thomasi bethunebakeri) raised with ants were significantly more likely to successfully pupate. Though tiny, ants may be an important piece to preserving rare Lycaenids such as the Puget blue and the closely related Fender’s blue (Icaricia icarioides fenderi).

Butterflies and nectar plants

Being a butterfly is hard work. Butterflies need lots of energy to fly, find mates, and lay eggs. So where does all this energy come from? Although butterflies do have some resources saved up from their time feeding on leaves as caterpillars, many species need to supplement their stores by collecting carbohydrate-rich nectar as adults.

Puget blue male nectaring on oxeye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare). If you look closely, you can see the proboscis (i.e. butterfly “tongue”) in the flower. Photo by Rachael Bonoan

We assessed the importance of adult nutrition for Puget blue survival and fecundity (how many eggs they can lay) by maintaining freshly emerged female butterflies on different diets in the lab. We found that regardless of diet treatment, Puget blue females lay about 20 eggs per day. But, even without flying, if fed water alone, they only live for about 5 days. Given as much sugar (i.e. carbohydrates) as they want, Puget blue females lived for about 25 days. This means that with carbohydrates collected from nectar, a female butterfly lives 5 times longer and thus, can lay 5 times more eggs! Our research suggests that we need to conserve both nectar and host plants to preserve and bolster Puget blue populations.

Puget blue female nectaring on Oregon sunshine (Eriophyllum lanatum). If you look closely, you can see the proboscis (i.e. butterfly “tongue”) in the flower. Photo by Rachael Bonoan

While our lab-based research shows that adult-collected nectar is in fact important for Puget blue population dynamics, little is known about which flowers they visit for nectar. We followed Puget blue butterflies to figure out what they like to eat.

Hanna following a Puget blue butterfly. Can you spot the butterfly on the lupine? Photo by Rachael Bonoan

It turns out, Puget blue butterflies can be picky eaters. Out of the 50+ species of flowers recorded on the prairie, we observed Puget blues feeding on only 9 species, many of which are introduced. Surprisingly, Puget blue females do not collect nectar solely from open flowers—they spent most of their time (60%!) probing closed flowers of their host plant. To examine this behavior further, we did a bit of chemistry and found that closed lupine flowers contain carbohydrates as well as amino acids (proteins!). Though there is still much to learn, amino acids may also help Puget blue females lay more eggs and/or survive longer.

From left to right, TOP: two closed Lupinus albicaulis racemes, open L. albicaulis raceme; CENTER: vetch (Vicia sativa), slender cinquefoil (Potentilla gracilis), spreading dogbane (Apocynum androsaemifolium), spreading snowberry (Symphoricarpos mollis); BOTTOM: yarrow (Achillea millefolium), false dandelion (Hypochaeris radicata), Oregon sunshine (Eriophyllum lanatum), oxeye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare). Photos by Rachael Bonoan