Partners for Fish and Wildlife: Voluntary habitat restoration on private lands, Post by Nick George, Photos as attributed.

Nick George is the Washington state coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Partners for Fish and Wildlife program. He has worked with private landowners to restore native habitat for the majority of his 10-year career in natural resources, including his time with the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS). Originally from Upstate New York, Nick has had the opportunity to work in multiple states including Texas, North Dakota, Montana, and Illinois. He is excited to find that South Puget Sound has such tremendous enthusiasm and opportunity for habitat restoration. At each stop, he has picked up a new tip or trick from practitioners and private landowners on how to restore habitat efficiently and effectively. Nick, his son, and wife currently live in Thurston County and are enjoying their first summer in Washington. For more information on the Partners program, please contact Nick at (360) 522-0545 or email Nicholas_george@fws.gov.

Partners for Fish and Wildlife: Voluntary habitat restoration on private lands

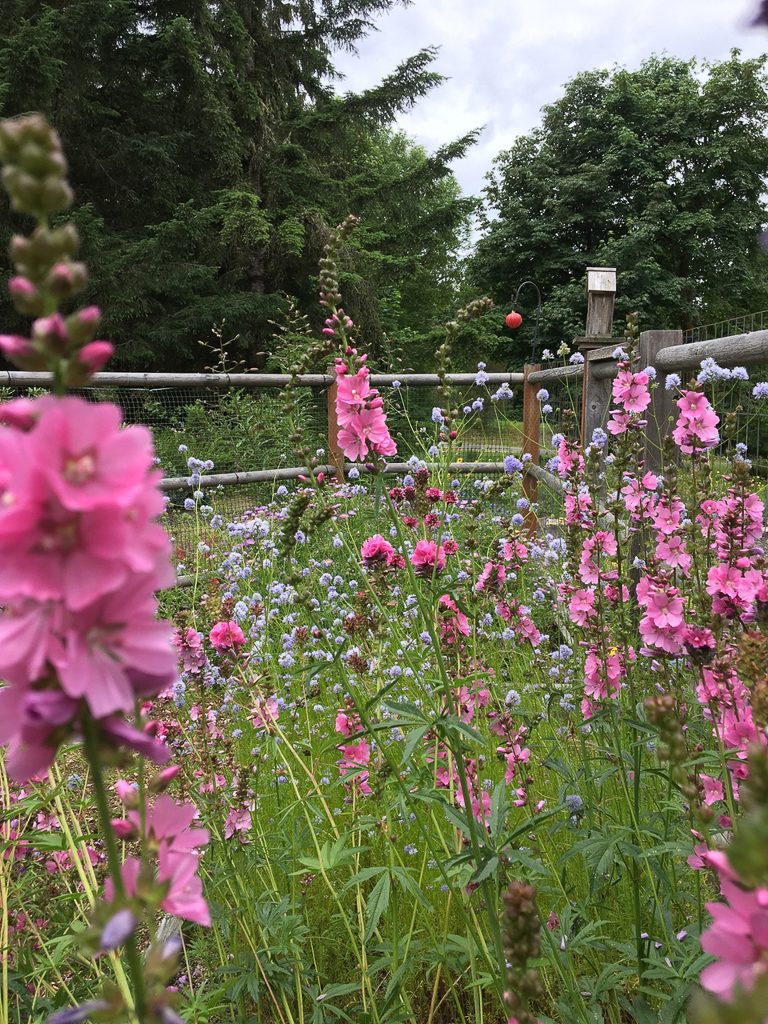

Hello, I’m new here. I was looking forward to meeting most of you during my first Prairie Appreciation Day, but obviously, that plan was spoiled due to our current situation. I come to you most recently from the Midwest, Illinois to be specific, and have worked extensively on restoring prairie and other habitats for native plant and wildlife species.

Although I am not yet an expert in restoring South Puget Sound prairies, many of the restoration concepts and habitat threats translate from my previous work (e.g. site preparation is key, habitat loss from human development can be overwhelming, invasive species are stubborn, etc.)

Nick George (USFWS Biologist) stands with a proud landowner after the completion of a project; Photo Credit: Debbie Newman/Illinois Natural Heritage

With this short post, I would like to first ask you a question – Are you familiar with the Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program? The Partners program (for short) is a great resource for private landowners who are interested in habitat restoration. Landowners have the opportunity to obtain technical, and in some cases financial, assistance for practices they are looking to implement on their property.

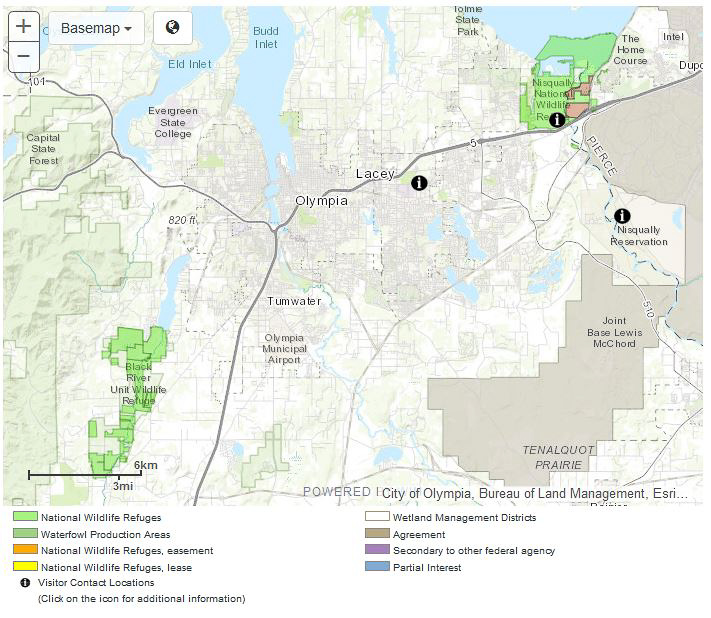

For a little over a decade, the Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program in Lacey has assisted with the restoration and enhancement of prairie habitat throughout South Puget Sound. The program has collaborated with the Center for Natural Lands Management (CNLM), the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS), and many other conservation organizations to successfully implement these projects on privately owned property. However, with the assumption the program may be new to your ears, or I guess eyes in this case, I will cover the basics.

The Partners Program is a voluntary habitat restoration program administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). All private landowners who want to restore and protect priority wildlife habitat areas on their property are eligible to participate. Current partners include farmers, ranchers, recreational landowners, land trusts, corporations, and local governments. The program helps private landowners conserve the Nation’s biological diversity and habitat integrity by reducing habitat fragmentation, increasing habitat for various plant and animal species, and supporting threatened and endangered communities.

Using prescribed fire to restore native prairie in Illinois; Photo Credit: Nick George/USFWS

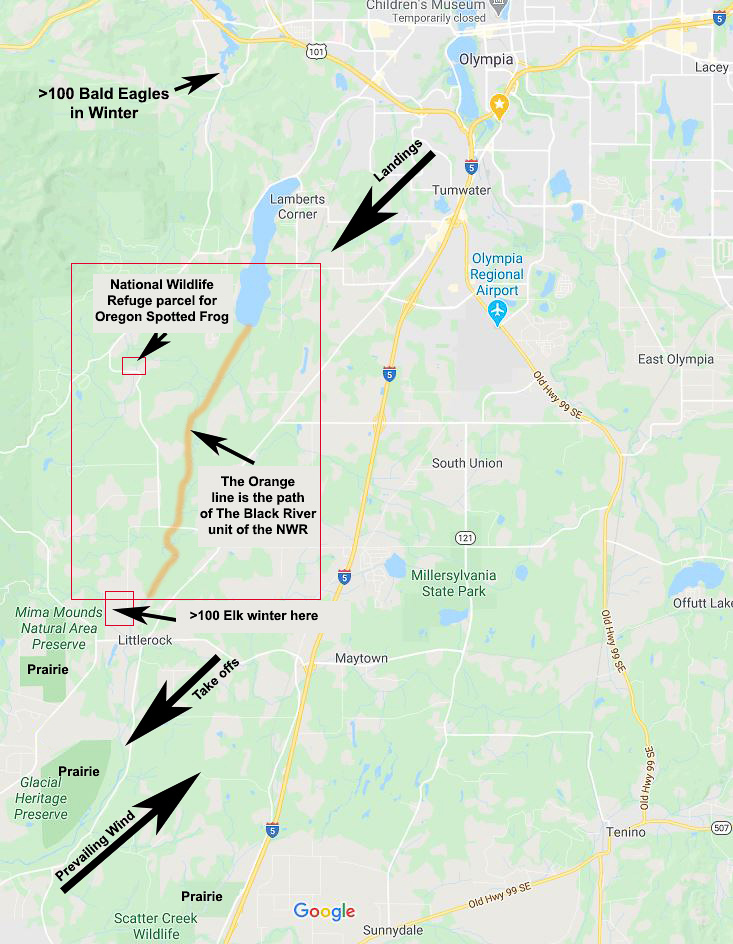

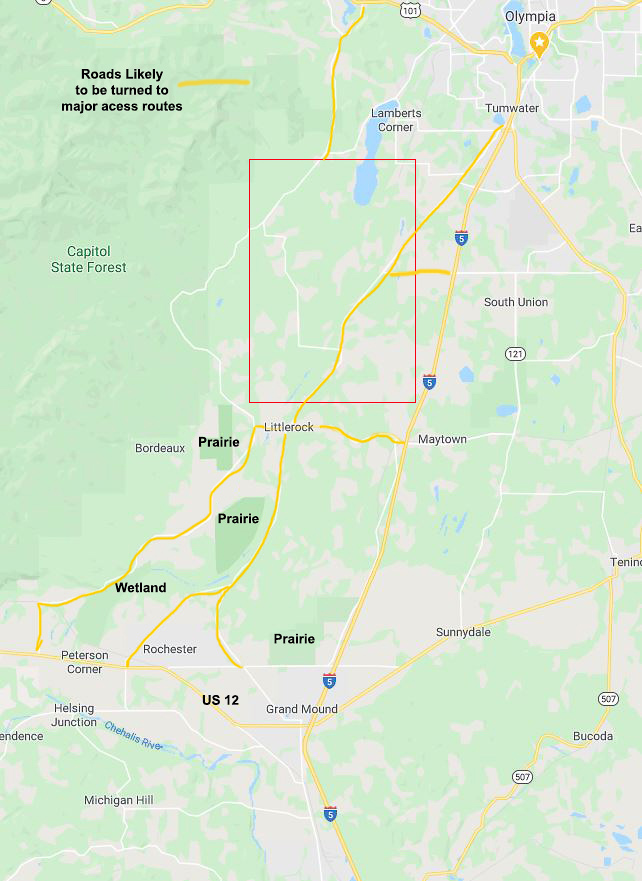

The primary goal of the Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program is for each restoration project to reflect the needs of the landowner, as well as the priorities set by the local U.S. Fish and Wildlife office. Participating landowners continue to own and manage their land to serve their needs while they improve conditions for wildlife. Here in South Sound, the Partners Program has multiple objectives. The first objective relevant to this forum is the restoration and enhancement of native prairie habitat to benefit priority species such as Mazama pocket gopher, Taylor’s checkerspot butterfly, streak horned lark, and Golden paintbrush, just to name a few.

Mazama pocket gopher; Photo Credit: USFWS

Restoring hydrology and enhancing shallow wetland and riparian habitat is another priority for the local Partners Program. This habitat type is critical for the federally threatened Oregon spotted frog to live a healthy and complete life cycle.

Oregon spotted frog; Photo Credit: Teal Waterstrat/USFWS

The projects that would be associated with these objectives could take place on a variety of property types. Although a 1,000-acre prairie reserve, 5-acre backyard for wildlife viewing, and 100-acre pasture for cattle produce different levels of benefit, all are equally important to protect and restore.

For more information on the Partners Program, or to find out what is available in your specific area, please feel free to contact me to discuss your property and potentially set up a site visit, when the situation allows.

Taylor’s checkerspot butterfly; Photo Credit: Zach Radmer/USFWS