Camas – Teachings in Reciprocity, Post by Elise Krohn and Mariana Harvey, Photos by Elise Krohn

Elise Krohn is the GRuB Wild Foods and Medicines Director and Mariana Harvey (Yakama) is the GRuB Wild foods and Medicines Program Manager

Camas – Teachings in Reciprocity

Camas prairies have offered Native People a food basket of game and edible plants since time immemorial. These open landscapes are home to many edible plants including camas, edible lily bulbs, bracken fern rhizomes, biscuit root, acorns from oak trees, and several types of berries. Medicinal plants including yarrow, kinnickinnick, violet, wild rose, and balsamroot flourish there. The prairies are also home to many species of butterflies, birds, and small land mammals.

Native stories and cultural practices passed down through the generations teach us how prairies have been cultivated like gardens. Many Native families historically traveled to prairies and camped for several weeks to harvest camas bulbs, cook them, and preserve them for later use. Cultivation techniques, including burning, aerating the soil with digging sticks, and weeding out unwanted plants, prevented the prairies from becoming forests. Without these practices, most of the prairies would have turned into dense forests thousands of years ago. Native People have taken care of the prairies and the prairies have taken care of them in return. This care continues.

What we see today are tiny remnants of vast prairies that were common just a few generations ago. European settlers made burning the prairies illegal because they saw fire as a destructive force rather than a life-giving one. In just a few generations, colonial land management practices such as farming and grazing reduced prairies to less than three percent of their former size. The prairie lands that had been managed and maintained by Native people for thousands of years were those very places that Euro-Americans settled and converted to prime farmland in places like Cowlitz Landing, Chehalis, and Centralia (then Cllaquato, Newaukum prairies), Boistfort, and other places where the deep, loamy soil prairies used to be.

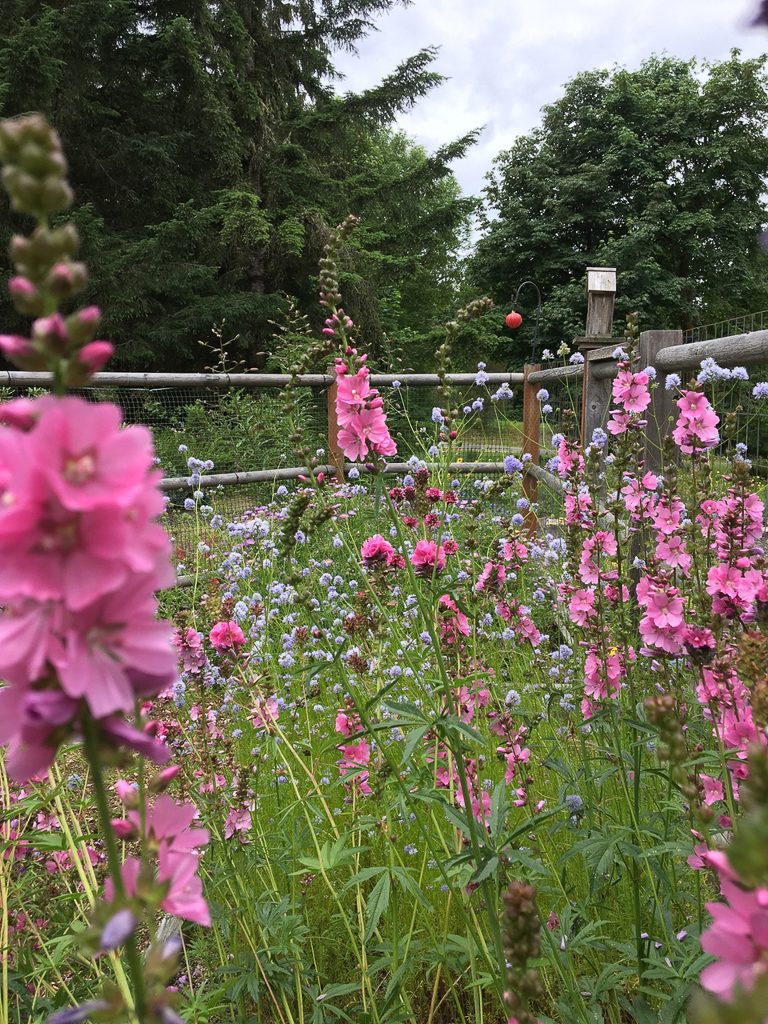

A Camas Prairie in full bloom. Photo by Elise Krohn.

Many tribes and other agencies are actively working to conserve and restore prairies and prairie foods. Camas is a main focus because it is a prized staple to many Northwest Native People. In fact, for many communities, it was the second most traded food next to salmon. Squaxin Island Tribe has planted camas in their garden and in fields on the reservation, and is working with several organizations on prairie conservation and partnerships for tribal members to access camas as a food. This year Squaxin Island collaborated with Delphi Community Club so that several tribal members could harvest camas in their traditional territory. Squaxin Island Community Garden program manager, Aleta Poste (Squaxin Island) says, “We have taken a moment to slow down and to think of what life is about and we are honoring life givers including camas. I see camas as being one of those life givers that has the ability to help our bodies heal. It’s really inspiring and empowering to be digging camas at Delphi School today because we get to look back and see that the legacy of our people is living on and that it continues today. One way that we practice giving back and having a reciprocal relationship with camas is when we harvest and we are digging the bulb. We are aerating the soil and we are enhancing the space around each bulb—giving those seeds the oxygen they need to breathe. It is giving them room to grow because we are removing the largest bulb. This is an ancestral practice that is being revived through many different communities.”

Aleta Poste (Squaxin Island Tribe), Photo by Elise Krohn.

Camas continues to be an important cultural food that is celebrated in First Foods feasts and other ceremonies. Tribal and multi-agency partnerships are an important step in support of the revitalization and care for cultural ecosystems like camas prairies, and to increase access of culturally significant foods for Northwest Tribes.

Other Names: common camas: Camassia quamash, giant camas: Camassia leichtlinii, Twana: Quamash, Qa’?w3b, Lushootseed: cabidac, Klallam: Ktoi, Upper Chehalis: quwm or quwam“

Identifying Camas: Camas has six-petaled, purple flowers and grass-like leaves. Bulbs grow four to eight inches beneath the surface and resemble small potatoes or onion bulbs. Giant camas (Camassia leichtlinii) has darker purple flowers and thicker leaves than common camas (Camassia quamash). Giant camas blooms a couple of weeks later and is more common east of the Cascades, in the San Juan Islands, and in Southern British Columbia.

Elizabeth Campbell (Spokane Tribe) demonstrating the use of a digging stick. Photo by Elise Krohn.

Food: Camas bulbs are dug in spring to early summer when the flowers or seeds are visible. This helps to distinguish it from a similar–looking poisonous plant, called death camas (Toxicoscordion venenosum), which has white flowers and similar–looking leaves and bulbs. Narrow t-shaped digging sticks that are made from hardwood, bone, antler, or metal make it possible to selectively harvest bulbs without damaging them or disturbing large sections of prairie. Harvesting also aerates the soil and allows moisture pockets to form, making it easier for new seeds to sprout.

Camas bulbs are cleaned by pinching off the stem where it enters the bulb and the roots from the base of the bulb. The brown outer skin peels off easily and you are left with a white bulb that resembles an onion.

Freshly dug Camas and the cleaned bulbs. Photo by Elise Krohn.

If camas has gone to seed, people sprinkle the seeds back on open soil. Harvesters are careful to only keep bulbs that are attached to seeds or flowering stalks, since death camas bulbs and leaves look almost identical.

Northwest Coastal Native Ancestors developed ingenious and efficient techniques for cooking camas that people still use today such as roasting over a fire, baking food wrapped in skunk cabbage or fern fronds in a pit or earth oven over hot coals, boiling in bentwood boxes or tightly woven baskets with hot rocks, and steaming foods with hot rocks in earthen pit ovens.

Before sugar was introduced, roasted camas was used to sweeten other foods, and many people continue this practice today. Cooked bulbs are often made into cakes and dried for later use. A compound in camas called inulin helps to support gut health and provides carbohydrates without raising blood sugar.

Tend, Gather and Grow Curriculum

Tend, Gather and Grow is a place-based curriculum that includes Northwest Coastal Native culture and plant traditions. It is intended to support the movements for Indigenous sovereignty and cultural reclamation, as well as encourage non-Indigenous communities to live more respectfully and sustainably in relation to the natural world. Tend has been designed by Native and non-native educators and is intended for use by Native and non-native educators and their students. Learn more about our work and team, here: https://www.goodgrub.org/tend-gather-grow

Reciprocity is a key teaching throughout the curriculum. A lesson on camas and a module on cultural ecosystems highlights how people care for plants and plants care for people. Students draw a camas circle of care and then draw their own circle of care. This helps students explore who they are connected to and how they might give back to their community of people, plants, animals, and places. Questions to reflect on include:

- Who do I care for, and who cares for me?

- I receive and appreciate the gifts of the land. What does this look like for me?

- I give back to the land to support future generations. What is my commitment?

Camas – A Plateau Native Story, as told by Roger Fernandes, Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe.

A long time ago in a village, there was a time of great hunger. There was no food to be found–no game to hunt, no plants to gather. The People were very hungry. There was a grandmother who heard her grandchildren crying because they were hungry. She was so sad that she had nothing to give them. She left the village and went up a hill nearby. She began to cry. She cried for her grandchildren. As she cried, she began to sink into the ground. After a while, she was gone. She was under the earth. Her grandchildren missed their grandmother. They wondered where she was and began to look for her. They climbed the hill, and as they reached the top, the granddaughter said, “Grandma is under the ground! I can feel her!” The children dug into the ground and found camas bulbs. Grandmother had become camas, and now the children and the People had food to eat. Camas is a main food of the Native people of the Plateau region. And that is all.

Camas flower. Photo by Elise Krohn.

Growing Tips: Camas can be easily started from seed and grown in a garden or schoolyard. It thrives in well-drained sandy or pebbly soil with full sun. It is best to start growing it in trays in a greenhouse, as it closely resembles grass. Keep camas root gardens carefully weeded to avoid confusion with grasses. Other companion plants include chocolate lily, violet, yampah (wild carrot), wild strawberry, yarrow, and Roemer’s fescue (a bunch grass). GRuB is currently developing a handout on creating a microprairie as part of the Tend, Gather and Grow curriculum. See https://www.goodgrub.org/wild-foods/wild-foods-medicine-resources for additional information.

References

Krohn, E. (2007). Wild Rose and Western Red Cedar.

Kruckeberg, Arthur R. The Natural History of Puget Sound Country. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press, 1994.

Leopold, Estella B. and Robert Boyd. “An Ecological History of Old Prairie Areas in Southwestern Washington.” Indians, Fire and the Landscape in the Pacific Northwest. Ed. Robert Boyd. Corvallis, Oregon: Oregon State University Press, 1999.

Turner, Nancy. The Earth’s Blanket. Seattle, The University of Washington Press, 2005.