Spring Colors, Butterflies, and Nectar at Mima Mounds Natural Area Preserve, Post by David Wilderman, photos as noted.

David is the program ecologist for the Natural Areas Program at the Washington Department of Natural Resources. He works on conservation, restoration, and monitoring of Natural Area Preserves and Natural Resources Conservation Areas around the state.

Spring Colors, Butterflies, and Nectar at Mima Mounds Natural Area Preserve

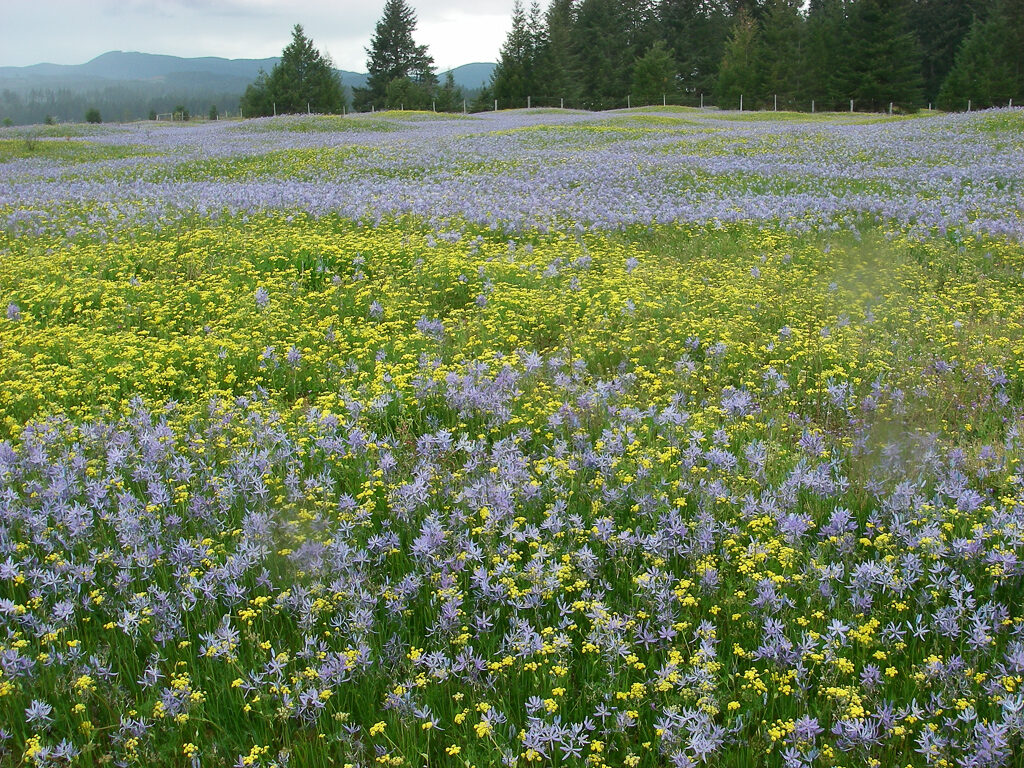

Early spring is perhaps my favorite time on the Mima Mounds Natural Area Preserve, when the heady days of full-on springtime are just visible on the horizon but not quite here. The earliest of spring blooms are just beginning to show as buds or fresh flowers that stand out against the background of that bright, young green that is only there for a short time before it becomes more lush and mature. On my latest visit to Mima Mounds in mid-March, the early plants were still awakening from winter and not yet flowering – still part of that bright green background. But within a few weeks, that will rapidly change. Henderson’s shooting star, western buttercup, spring-gold, western saxifrage, and wild strawberries will start to light up the landscape with magenta, yellow, and white, followed by the camas bloom that usually starts in late April. If you’re lucky enough to catch some of these together, in profusion, it can be quite a sight!

Shooting Star, Photo by Aaron Barna

Camas and Spring Gold after a Prescribed Burn, Photo by David Wilderman

On our occasional bluebird days this time of year, or even during a brief sun-break on an otherwise rainy day, bumblebees and other insects can be seen getting their first taste of prairie pollen and nectar. It’s always amazing to me how much the prairie can suddenly come alive during a brief break in the clouds, rain, and wind. One of the other early bloomers, though not strictly a prairie plant, is kinnikinnick – a sprawling, low-growing woody plant that often forms mat-like patches. If you’re lucky, you might spy a small, brown butterfly fluttering around these patches — the Hoary Elfin, distinguished by the frosty coloring (“hoary”) on the outer portion of its wings. This butterfly, while not the most striking to look at, is interesting in its specialized life history. It essentially lives out its entire lifespan within patches of kinnikinnick – perhaps even within a single patch. Adults nectar on the flowers and lay their eggs on the season’s fresh new leaves, which the larvae then feed on after hatching a week or so later. Mima Mounds has one of the larger known populations of Hoary Elfins, one of a number of butterfly species found in our prairies that have declined significantly from their historic numbers. The trails near the interpretive building on the preserve are a good place to keep your eye out for these little lepidopterans, although it takes a sharp eye as they are pretty cryptic.

Kinnikinnic Flowers and Fruit, Photo by Rod Gilbert

Hoary Elfin Butterfly on Kinnickinnick, Photo by David Wilderman

As with most of our remaining South Sound prairies, rare or declining butterflies like the hoary elfin are important conservation features and the focus of many management efforts at Mima Mounds. In addition to the hoary elfin, Mima Mounds harbors important populations of several such species including a few that won’t be seen for a few months – the Great Spangled Fritillary, Zerene Fritillary, and Oregon Branded Skipper. Adults of these species fly during high summer – July and August – with the females seeking out violets (the Fritillaries) and grasses (the Skipper) on which to lay their eggs.

Early Blue Violet, photo by David Wilderman

Nectar can provide an important energy boost during this time, helping extend their lifespan and perhaps improving their reproductive capacity. However, nectar tends to be in short supply during mid to late summer on the prairies, as most of our native wildflowers have their peak bloom in the spring. So what do these butterflies nectar on? Among the native plants they might search out are white-top aster (a rare plant limited to Pacific NW prairies), spreading dogbane, showy daisy, and pearly everlasting, although these are often sparse, only overlap with the early part of their flight season, or do not flower abundantly on the prairies. Most often, we find them nectaring on the flowers of weedy, non-native plants like tansy ragwort and Canada thistle. This obviously presents a bit of a conundrum for managing these sites, requiring a balance between controlling these species to meet legal requirements and keep them from spreading within the prairies – and keeping enough of them around to help supply nectar to hungry summer butterflies.

Oregon Branded Skipper on Tansy Ragwort, photo by Ann Potter

Zerene Fritillary on Tansy Ragwort, photo by David Wilderman

One of the efforts we’ve been focusing on recently at Mima Mounds is trying to diversify and boost populations of native late-season nectar plants, with the hope of eventually “weaning” the butterflies off of the non-native species. Mostly this is done by including these plants in our seeding and planting mixes after prescribed burning; but we’ve also begun adding them to smaller, targeted areas on the prairie / forest edge in hopes that some shading will help the flowers persist even longer into the season. Last fall, for instance, we planted and seeded a number of areas along the forest edges with pearly everlasting, spreading dogbane, and a native thistle (short-styled thistle) to see if we can establish more of these plants on the site — and if the butterflies will in fact use them rather than the non-natives. So, if you’re out on the Mima Mounds on a warm summer morning, or even a hot afternoon in July or August, watch for butterflies and see what plants they might be drinking nectar from. Hopefully, it’s one of our natives!

Spreading Dogbane, Photo by David Wilderman

If and when you do visit, be sure to check out the signs and illustrations at the interpretive building, aka “the mushroom” or “the concrete mound” (the latter was in fact the idea behind the design). They highlight various aspects of the site, including plant and animal species, prairie ecology, mound-origin theories (that’s a long story of its own), and some of the uses and management of prairies that has taken place for centuries, if not thousands of years. And don’t forget your Discover Pass for parking!