Wildfires and Prescribed Burns, Post by Dennis Plank with input from Mason McKinley, Sanders Freed, and Ivy Clark. Images by Dennis Plank and Ivy Clark

Dennis has been getting his knees muddy and his back sore pulling Scot’s Broom on the South Sound Prairies since 1998. In 2004, when the volunteers started managing Prairie Appreciation Day, he made the mistake of sending an email asking for “lessons learned” and got elected president of Friends of Puget Prairies-a title he appropriately renamed as “Chief Cat Herder”. He has now turned that over to Gail Trotter. Along the way, he has worked with a large number of very knowledgeable people and picked up a few things about the prairie ecosystem. He loves to photograph birds and flowers.

Wildfires and Prescribed Burns

The Mima Fire of the afternoon of September 8th caused us to be evacuated and was stopped on the other side of the road we live on.

View Looking toward Mima Road from our driveway after the burn. We’re on the unburned side. Photo by Dennis Plank

The Fires:

In the aftermath of this rather traumatic event, I started to consider the difference between the controlled burns I was familiar with seeing and this event. To help clarify my picture, I sent an email to Mason McKinley, the long time burn boss for the Center for Natural Lands Management and an expert in controlled burns of prairie habitat. Here’s a copy of my question and his reply:

To Mason:

The part of the Mima fire east of Mima road ended at the road I live on. We’re on the safe side so we suffered no damage. However it occurred to me to white a PAD Blog post on how not to do a controlled burn. When I proposed it to Sabra, her first question was: “How hot was it? Was it hotter than a controlled burn?” Thinking that over and taking some pictures of various locations today I had the thought that it would be good to get an expert to come down and look it over and tell me how it compared with a controlled burn.

To Dennis:

“Interesting question. You can answer the question of “was it hotter than a controlled burn?” in many ways. From a safety perspective, it was definitely drier and windier that day than a day we would pick to burn. As fuels cure and dry out, and as wind adds more oxygen, the “energy release component” increases for any given fuel. This just means that more of the fuel is completely, rather than partially consumed and the fire needs to use less energy to first drive off water from within the fuel to get the volatile gases to release. That is the same thing that explains why damp firewood doesn’t burn as hot as bone dry wood and it leaves more residue in your chimney because fewer of the released gasses actually get hot enough to combust. So, it is scientifically reasonable to say that more energy was released per unit of fuel on that day than on one of our cooler, more humid and less windy burn days.

But really, the difference in heat released itself might not be a reason not to burn. With cured and dried flashy fuels, they just burn hot and a few extra degrees of temp or less RH doesn’t make a huge difference (though it can lead to more smoldering moss and heavy fuels). Sometimes you want a lot of heat and consumption – you just want to be able to control it. In this case, it was the wind in particular that was bad and the low RH means that broom and fir trees are going to be better able to send embers to quickly create spot fires that in turn can spread fast. Woody broom and firs are also more likely to get really hot and throw big flames in those conditions too (which I think describes the old race track). We would not burn here with that RH and how cured the fuels are and we would have prepped broom and firs to facilitate containment prior to burning. But I have burned other places where they are ok burning with RH in the teens. In the Midwest grass areas, they are not even afraid of stronger winds. It just depends on the burn objectives, types of fuels, what the containment lines are like and the various risks.

Even with that wind and those flashy fuels, if there had been an engine or three on site ready to respond right away when the transformer blew, chances are they would have been able to stop it quickly or hold it at roads or deploy other tactics. That is a huge difference between wildfires and RX. With RX we have the luxury of planning, scouting, prepping, getting equipment and firefighters lined out to address the biggest risks before there is even fire on the ground. Coming into an unscouted situation that has already been burning for 10-30 min, with flashy fuels, obscuring smoke, houses, fences, panicked residents, different fire teams from different agencies showing up at random times adds several magnitudes of chaos.”

So from the point of view of the person controlling the burn, it’s the lack of preparation that makes the real difference between a controlled burn and a wildfire.

The discipline of a controlled burn. Photo by Dennis Plank

Mason mentions the panicked residents. While I didn’t see any examples of real panic amongst my neighbors; everyone wanted to get back in to see their property and check on animals. They let people in for awhile (we happened to be at dinner then), and when we came back they had quit letting people in because the congestion caused by all the residents on these small side roads was impeding the mobility of the fire crews (of which there were an incredible number, especially considering how many worse fires were in existence at the time). This seems to me a good reason for evacuating residents in and of itself: it gives the fire crews a free hand to do their job and they did it incredibly well in this instance with only one house lost, even though the fire was right up to the walls of several.

One of several houses where the fire burned right up to the house. This particular house had dense shrubbery around three walls. Photo by Dennis Plank

In contrast, in a controlled burn, everyone knows what’s happening, the crews are in place, firebreaks are established and fall-back plans have been developed and are known by the fire crews.

Aftermath:

With the Mima fire, the event essentially ended with the fire being under control and the elimination of hotspots, an activity that lasted from Tuesday, when the fire started and didn’t cease until the following Monday. This seems to be typical of wildfires.

DNR Helicopters spent most of a day after the fire dumping water on the field surrounding a horse facility that spreads it’s manure on the fields. It smolders really well. Photo by Dennis Plank.

A fire crew going in to check for hot spots after the fire. Photo by Dennis Plank

I asked Sanders Freed, the Center For Natural Lands Management’s south sound preserves manager and one of his people Ivy Clark, a regular contributor to this blog, for input on what happens after the burn. Sanders, as is typical of him was very brief and to the point. Here’s his reply:

“The general prescription after a fire is an herbicide application- right when things pop back up, which are mostly non-native and invasive like hairy cat’s ear and ox-eye daisy. Then you seed back natives, usually with a drop seeder followed by a harrow to increase soil/seed contact. That’s about it- then you wait for spring to see what grows! There can be alterations of the plan for specific species and burn intensity- but that’s the gist.”

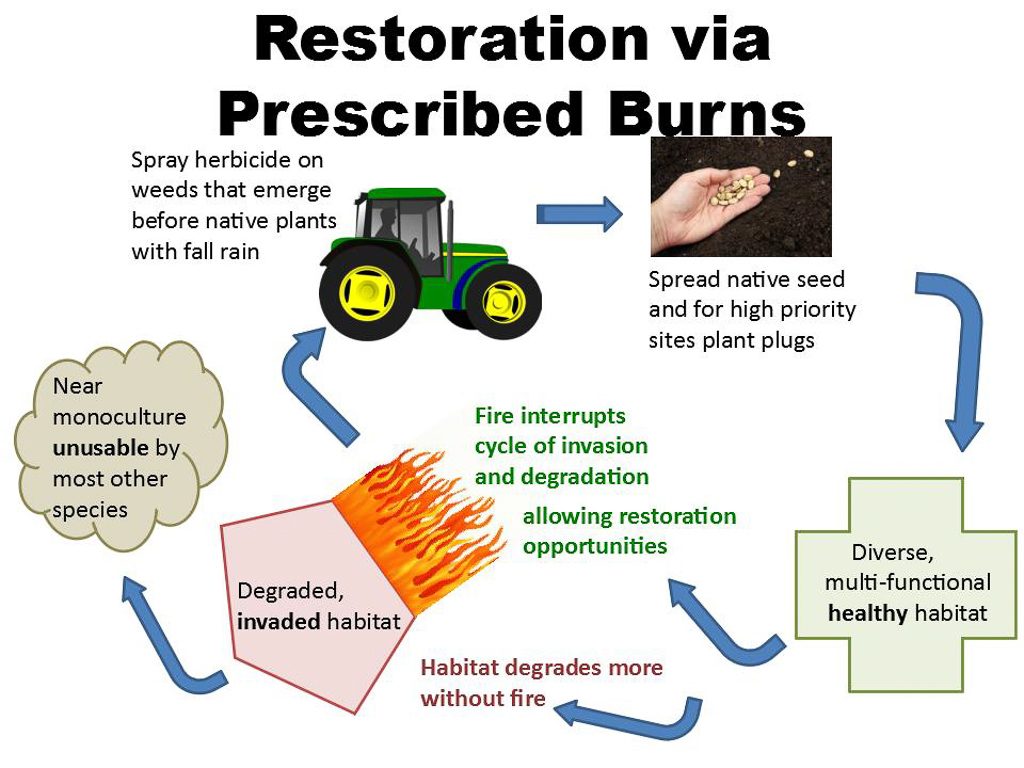

Ivy provided more detail and some graphics to help clarify the process:

Restoration with Burns. Graphics by Ivy Clark

“As we are back in the prescribed burning window for habitat restoration, we can see that essential irreplaceable part of prairie restoration that’s scary and exciting all in one. Fire doesn’t just kill weeds like broom and European hawthorn, it clears debris (fuel as we call it) that covers up ground and smothers more sensitive plants. Native prairie plants are adapted to germinate their seeds on exposed soil and when fire is kept out for too long, moss and duff and grasses fill in all the gaps they would need to keep reproducing. Fire clears ground for natives to get ahead. It also knocks back weeds that don’t actually die in fire, like hairy cat’s ear and blackberry.

Controlled Burn in Progress. Photo by Ivy Clark.

Crews Governing a Prescribed Burn. Photo by Ivy Clark

Since weeds are invasive because they tend to grow faster and earlier than natives, they will start regrowing before native plants come back up or seed newly encouraged by the fire germinate.

Hairy Cat’s Ear after a Fire. Photo by Ivy Clark.

This gives a great opportunity to spray herbicide over the burn area so that only weeds will die, making even more room for natives. With this newly cleared area and just about to emerge natives as fall rains begin, we can augment the native population with more seeds, possibly returning species that had been extirpated, further increasing native diversity and habitat function. And since it’s a prairie, it’s all the more beautiful as well. Each site gets a tailored mix of seeds, mostly forbs and plenty of annuals which suffer the most in degraded areas.

A Selection of Seeds to Be mixed with Fescue for Seeding after a Burn. Photo by Ivy Clark.

And of course Roemer’s fescue along with a few other native grasses. For high quality high priority sites that may get a checkerspot release within a year or two, we will also add thousands of plant plugs to boost the population of a few important flowers for the butterflies, ready to bloom for them the following spring.

Volunteers Planting Plugs on Glacial Heritage. Photo by Dennis Plank.

Fire is the start of this chain of restoration events that return health to the area that you just can’t get with any other method. It also kills a few established conifers and releases any oak seedlings struggling in their shade to grow faster into healthy full oak trees.”

And this is just part of the restoration process because fire rarely kills all the Scotch Broom and follow up pulling and/or spraying is required. And, of course this is not a one-time activity. On average, the prairie needs to be burned every four years or so to keep it in a healthy condition.

To me, the saddest thing about a wildfire like this (aside from loss of houses and lives) is the missed opportunity to put them to good use. This fire, coincidentally, followed a corridor from the south end of the Mima Mounds Natural Area Preserve to a within a five acre parcel and an old gravel pit of Glacial Heritage Preserve.

Some idea of the scope of the Mima Burn. Photo by Dennis Plank

Local Prairie Restorationists have long dreamed of connecting the two and most of the connecting properties are small private parcels that are not farmed, though they might have a few horses or other animals on them. Getting those parcels restored to healthy prairie would go a long way toward creating that larger ecosystem that’s more resilient to damage and degradation. It would take a lot of education of the local landowners and some means of accessing the herbicide and seeding equipment (and seeds-which are not cheap!) for the follow-up treatment. But if it could be done, it might be a way of turning what look like disasters into long term benefits both for the prairies and for the people who now live on them. We’re going to have more of these. Almost every summer brings a scary period where we’re afraid to leave the property for fear of fire and it’s only been a few years since the Scatter Creek fire just a few miles south of here. They’re going to happen, but they can be useful and good native prairie habitat doesn’t burn with the intensity of the non-native grasses and Scotch Broom.

DC-10 Adapted for Fire Retardant Dumping Turning for another Pass at the Scatter Creek Fire in 2017.