Bats on the South Sound Prairies, Post by Greg Falxa, photos as attributed.

Greg is a member of Cascadia Research Collective and has partnered with

CNLM on bat projects since 2006. He coordinates the bat station for

Prairie Appreciation Day.

Bats on the South Sound Prairies

Most of the nine species of bats in western Washington are nightly visitors to our south Puget Sound prairies. The inventory of bat species on the prairies are essentially the same as in nearby forest, riparian and urban habitats, although their preferred habitat may vary throughout the annual cycle. For mammals of their size they are extremely mobile, with most species traveling from a few to many miles each evening to their favored foraging locations. Being so mobile allows bats to day roost in one habitat – like agricultural buildings, or hollow snags – and “commute” in the evening to a completely different habitat to forage.

A Big brown bat nursery colony in a barn on Littlerock Road (Photo: G. Falxa)

This mobility works out well for bats feeding on insects over the prairies, because most of our prairies are a bit short on suitable roosting structures. For daytime roosting, bats generally need dark, secluded locations that are safe from predators and meet certain temperature conditions, like structures that don’t get too hot on our nice sunny days. Species that form small colonies like California bats (Myotis californicus) might find this in old decadent trees or snags, while species that form colonies of hundreds of bats, like Little brown (Myotis lucifugus) or Big brown (Eptesicus fuscus) bats will typically find the conditions they need in barns, bridges, or attics of buildings. During the June and July pupping season, the nursery colonies need additional amenities for the 4 to 6 weeks that the pups cannot fly. A warm roost with extra safety from humans and predators like cats and raccoons can be hard to come by for a large group of pregnant bats, so when a suitable location is found it tends to be used every year by the colony. The juxtaposition of the South Sound prairies with agricultural and forest lands, and JBLM, creates a good environment to support bats that can roost near the prairies and include the prairies in their foraging options.

A Silver-haired bat netted (then released) at JBLM (Photo: G. Falxa)

Depending on the insect hatch on a given day, an individual bat may forage along a tree-lined creek or at the forested edge of a prairie, or both habitats in a single night. Some species, like the Yuma bat (Myotis yumanensis) will focus nearly all of their foraging low over open water, usually a lake like Capitol Lake or Black Lake, but during the mid-summer months many can be seen flying low over the Black River, which is almost lake-like along various stretches, including adjacent to Glacial Heritage Preserve. Most species of bats avoid foraging in the open prairie, probably because it is more exposed to being hunted by owls and raptors than forest edges. However, our 3 largest species – the Hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus), Silver-haired bat (Lasionycteris noctivagans), and Big brown bat – can be regularly heard or seen in the prairie sky. Using ultrasonic bat detectors placed at the prairies over the past 12 years we have documented nearly all of the 9 bat species in this region, and the only species not yet recorded at the prairies – Fringed myotis (Myotis thysanodes) – has been recorded less than 2 miles from Mima Prairie in the Capitol Forest.

A roosting Townsend’s big-eared bat (Photo: R. Davies)

Shortly after the Mima Creek Preserve was acquired, the discovery of a lone female Townsend’s big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii) in an out building led to a 2-month investigation to locate its nursery colony. This species is relatively rare, and no colonies were known in the Black River watershed. By radio-tagging and tracking several individuals in sequence (each radio tag lasted 3 weeks) we finally located a colony of approximately 100 Townsend’s in the attic of a little used building near the Chehalis River. They were foraging and occasionally roosting all along the Black River drainage, feeding in the canopy of trees along forest – prairie boundaries.

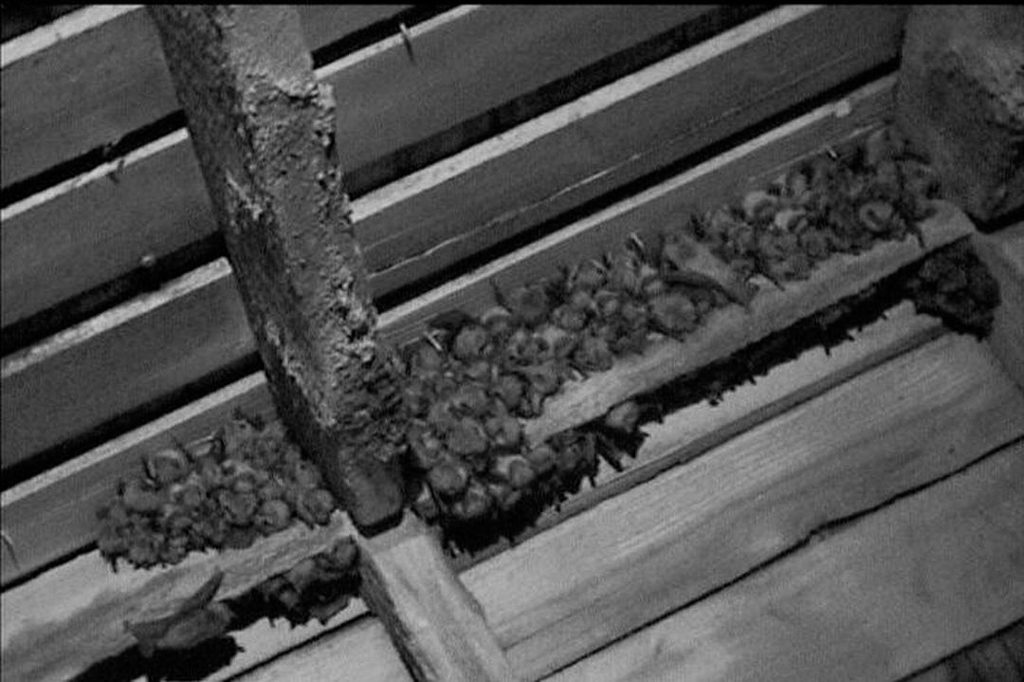

Nursery box installed at Wolf Haven (Photo: G. Falxa)

Little brown bats (Myotis lucifugus) have occupied the bat box structures that have been constructed and erected at glacial Heritage, Wolf Haven, and various JBLM sites. For the past 10 years CNLM’s Sanders Freed has worked with me to develop bat house designs that are effective in this region. With support from US Fish & Wildlife, JBLM, and CNLM, we’ve experimented with designs to be used as a “nursery box” for the female bats to have a safe place to have their pups and get them to their volant stage, at about 6 weeks of age. The “evolved” design was installed at Wolf Haven in 2012 and has had over 400 adult bats in it the past few years. The bat house sits on the edge of the prairie forest interface, which is likely one of the reasons it is has been a success.

It is important to remember that each species has different habitat and roosting needs, and that a bat box built for one species may be wholly unsuitable for another. The photo below helps illustrate this – Sanders Freed is shown constructing a bat roost structure designed for Townsend’s big-eared bats, located near Muck Creek at the edge of the JBLM Artillery Impact Area. Townsend’s never use the crevice-type of bat boxes, favoring abandoned cabins, roomy attics and similar spaces.

Construction of the “Bat Temple” at JBLM (Photo: G. Falxa)

In addition to habitat loss (both foraging and roosting) a concern for our bat populations has been the arrival of white-nose syndrome from the eastern U.S. In 2016 we discovered bats infected with the fungus that causes the disease which kills bats, primarily in the winter during hibernation. So far it appears to be affecting bats in the Cascade mountains and foothills, and has not yet been detected in Thurston County.

Links:

Some bat videos at local points of interest:

https://www.youtube.com/user/batsalot/videos

Washington Dept. of Fish and Wildlife:

Western Bat Working Group:

A very impressive article. With nine species, representing at least five distinct genuses (one family?), is there subspeciation or hybridiztion going on? They are all insect eaters? – so how do they divvy up the habitat? Are the colony members tied to a location, or to each other? Are there communication differences between colonies?

With such a fascinating topic, I look forward to more posts. Thanks so much!

I get what you’re trying to do there Sabra. Yes, I’ll work on a follow-up if folks are interested.